Written by Yong Chee Keita Sin and Raghav Narayanswamy

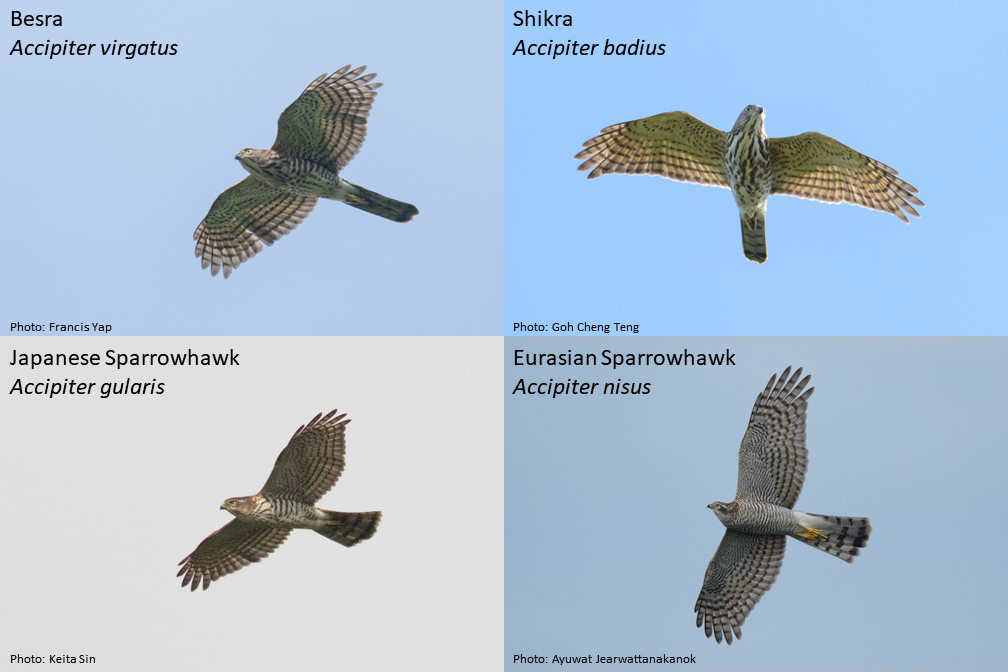

Sparrowhawks, from the genus Accipiter, are notorious for their identification difficulty. In Singapore, the Japanese Sparrowhawk Accipiter gularis and Chinese Sparrowhawk A. soloensis are commonly observed during migration, while Besra A. virgatus, Shikra A. badius, and Eurasian Sparrowhawk A. nisus make rare appearances for the persevering few. The only resident Accipiter in Singapore is the Crested Goshawk A. trivirgatus. (Fun fact, the Crested Goshawk is placed in a separate genus Lophospiza by some as they are genomically separated from the rest of the Accipiters based on currently available evidence.)

A combination of features is always needed in Accipiter identification including wing shape, body shape, and the number of “fingers” (the number of elongated primary feathers). The Crested Goshawk for one has distinctly rounder wings compared to all other Accipiters and is often seen in flight with their heavily feathered “fluffy” undertail exposed. The Chinese Sparrowhawk too is unique in having only four “fingers” with distinct black tips across all ages and a more tapered looking wing. The plumages of Accipiters can of course be identification useful features too, but are too often very similar across many species, especially in juveniles. For example, juvenile Japanese Sparrowhawks have fairly similar underparts to Besra and Shikra (and juveniles of the latter two are almost indistinguishable, unless the yellow eye ring and/or thick black tail bands – diagnostic for Besra at least based on currently understood identification features – are seen).

Our individual species pages and visual raptor ID guide cover numerous identification features that can be useful in identifying the raptors in Singapore beyond just Accipiters. However, every now and then, difficult birds show up that push our boundaries and challenge our knowledge of raptor identification.

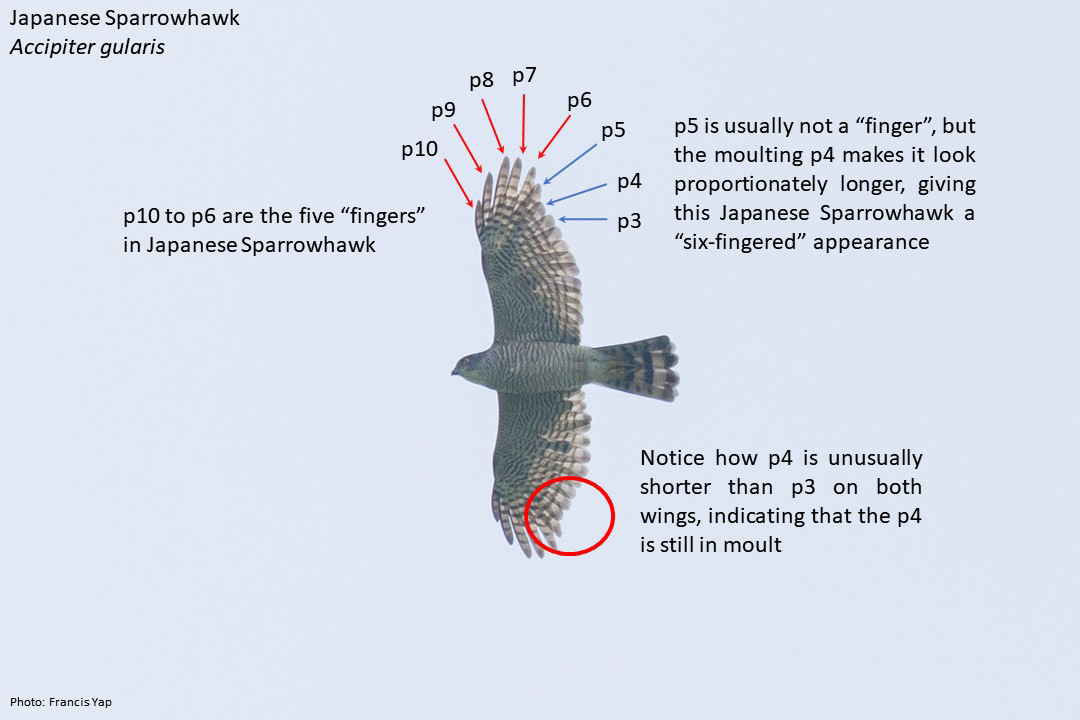

One of the problems that often confuse people is moult – sometimes, Accipiters with moulting primary feathers appear and cause their apparent number of “fingers” to change, causing identification issues. Here’s an example of an Accipiter with six apparent “fingers”.

The only Accipiters in Singapore with six “fingers” are the Crested Goshawk and Eurasian Sparrowhawk, but the plumage on this bird is incorrect for a Crested Goshawk, which would never have barred plumage at any age. Its wings are not round enough either. The bird superficially resembles the very rare Eurasian Sparrowhawk, but the body is too small, tail is proportionally too short, and wings do not look massive enough. The photographed bird is instead the common Japanese Sparrowhawk with moulting primary feathers (p4, the 7th finger from the leading edge) that is causing the sixth “finger” (p5; the 6th finger from the leading edge) to look proportionally longer. A similar bird like that showed up last season as well, which caused a fair bit of identification controversy, and the Singapore Bird Records Committee voted that it was likely to be a Japanese Sparrowhawk as well.

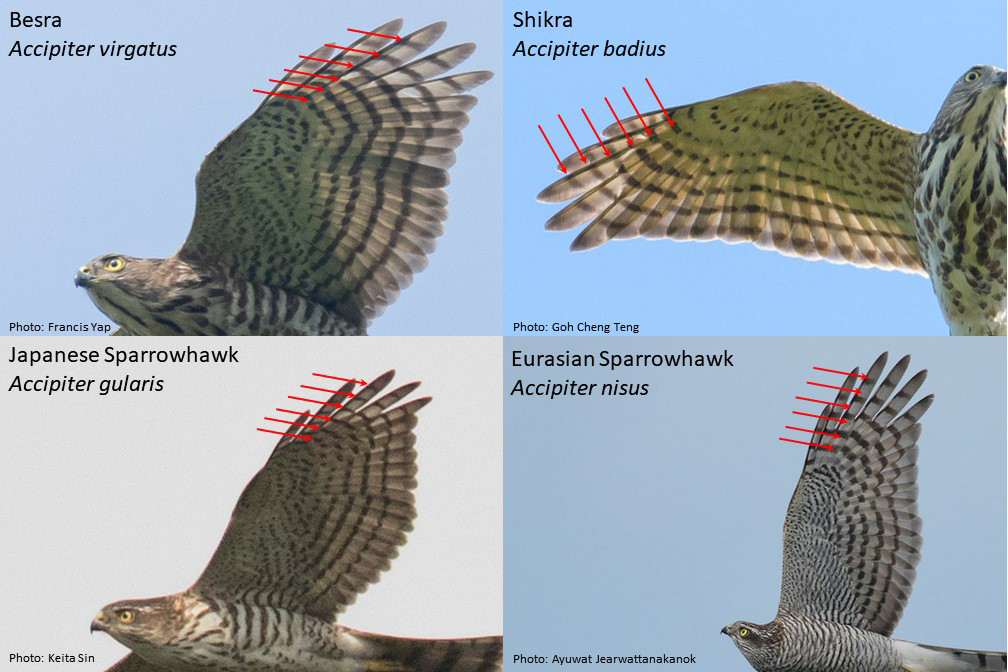

While researching the identification features of these sparrowhawks, we referred to a collection of reputable field guides and other documentations (e.g. Billerman et al., 2022; Eaton et al., 2021; Ferguson-Lees & Christie, 2001; Puan et al., 2020; Robson, 2014; Treesucon & Limparungpatthanakij, 2018; Wells, 1999 and more; as well as the few documentations online by trustworthy sources), and noticed a seemingly consistent feature that has not been mentioned in any literature before – the number of bars on the primaries of the fingers. The Japanese Sparrowhawk seems to have consistently more black bars, giving the primary wing tips a slightly denser appearance compared to Eurasian Sparrowhawk, and especially so to Besra/Shikras.

To examine this hypothesis we examined ~25 online photographs of each of the four species with nice underpart profiles, and counted the number of black primary bars present on each bird. For Besra/Shikra, due to the extreme similarity of their immature plumage, we only selected photographs that were either from reputable observers, or where the diagnostic features (eye ring, tail band) were visible. Additionally, adult Shikras are easily distinguished based on a combination of other features, so we only included immatures for this work. For all species, photographs were only considered if they were taken in Thailand, Peninsula Malaysia and Singapore to avoid any effects of subspecific variation.

Our quick survey shows that, indeed, the number of primary barring is a useful suggestive feature in at least distinguishing the Japanese Sparrowhawk from the other three, by in general having more primary bars. Looking at p8, for example, we can see that most Besras, Eurasian Sparrowhawks, and Shikras have five or fewer bars, where most Japanese Sparrowhawks have six or more. A qualitative feature that we also noted, but did not measure, is that Besra and Shikra have thicker primary bars (possibly thicker and more equal-width in Besra compared to Shikra), while Shikra’s bars are usually narrower on the inner part of the primary feathers. Japanese Sparrowhawks appear to have narrower primary bars overall. Having said that, there still are individuals that show overlaps, such as those in the collage below.

In general, with decent photographs available, the identification of these birds are straightforward enough that primary bars likely need not be considered. Then again, given that Accipiter ID more often than not relies on the combination of multiple features, we believe that it is at least a suggestive feature in distinguishing the Japanese Sparrowhawk from Eurasian Sparrowhawks/Besra/Shikra. Such a feature has in fact recently been shown to be a useful identification feature between Common Cuckoos and Himalayan/Oriental Cuckoos!

Of course, it needs to be mentioned that the identification of these birds from single photographs alone is oftentimes far more complicated than necessary – we have seen way too many examples of the body, wing and tail proportions suggesting one species in a picture, and a separate one in the next photo series. Funnily enough, heat waves can also cause features like the width of tail bars to be distorted. We strongly recommend everyone to take many pictures of the birds in the field (underparts from multiple angles, and even upperparts if possible), and also take note of as field marks as possible such as flapping pattern and apparent size, although this can be extremely difficult without any scale of reference..

We hope that this article helps to raise awareness of this seemingly undescribed identification feature and are excited for discussions and potential projects to discover more about these birds. If there is any literature that mentions these features, or any other useful field marks, please direct them to us as well.

Acknowledgements

We thank Francis Yap, Goh Cheng Teng and Ayuwat Jearwattanakanok for their photo contributions, and Dillen Ng for comments.

References

Billerman, S. M., Keeney, B. K., Rodewald, P. G., & Schulenberg, T. S. (Editors) (2022). Birds of the World. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Eaton, J. A., van Balen, S., Brickle, N. W., & Rheindt, F. E. (2021). Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago: Greater Sundas and Wallacea (Second Edition). Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Ferguson-Lees, J. & Christie, D.A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

Puan, C. L., Davison, G., & Lim, K. C. (2020). Birds of Malaysia: Covering Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysian Borneo and Singapore. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Robson, C. (2014). Field guide to the birds of South-East Asia (Second Edition). Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Treesucon, U. & Limparungpatthanakij, W. (2018). Birds of Thailand. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Wells, D. R. (1999). The birds of the Thai-Malay peninsula (Vol. 1). Academic Press, London.