Imagine a world where you could predict the arrival of your favourite migratory bird, get immediate identification help for an unfamiliar bird, and contribute to science and conservation just by being out in the field. I have some fantastic news for you…that’s the world we live in now!

BirdCast is a forecast map that utilises weather forecast maps to model bird migration. Scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are able to track data on how birds travel, allowing myriads of research ranging from the effects of climate change, to single events such as the influences of hurricanes on bird movements to be projected. One of the key components that makes BirdCast functional is data from eBird. The most rudimentary form of data – actual bird encounters from the birdwatchers in the field – are combined with highly intricate weather surveillance infrastructure, to make fairly accurate predictions of bird migration. A well-known example of how eBird data has transformed the birding experience of beginners is the Merlin platform which uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) to identify birds. Users simply need to upload a photograph or sound recording of the bird and the AI will suggest several potential candidates. This complex AI did not magically appear, though – it was made possible through feeding tons of photographs and sound recordings to the computing system, once again with the help of eBird data. These platforms allow birding to be much more targeted, focused, and friendly, both for beginners and the most hardcore of birdwatchers. Sounds great, doesn’t it? Now here’s the catch: at present, BirdCast is only available in the United States. The platform was first launched in 2018, and research is still concentrated in the area where eBird data is most abundant. On the other hand, although Merlin started out being only available in United States initially, there is now a package for Singapore, though it still struggles with similar looking birds such as Phylloscopus warblers. With enough contribution from the regional birding community, other platforms such as BirdCast will hopefully be made available to us as well. A massive way you could contribute to improving the precision of these tools is by contributing to eBird.

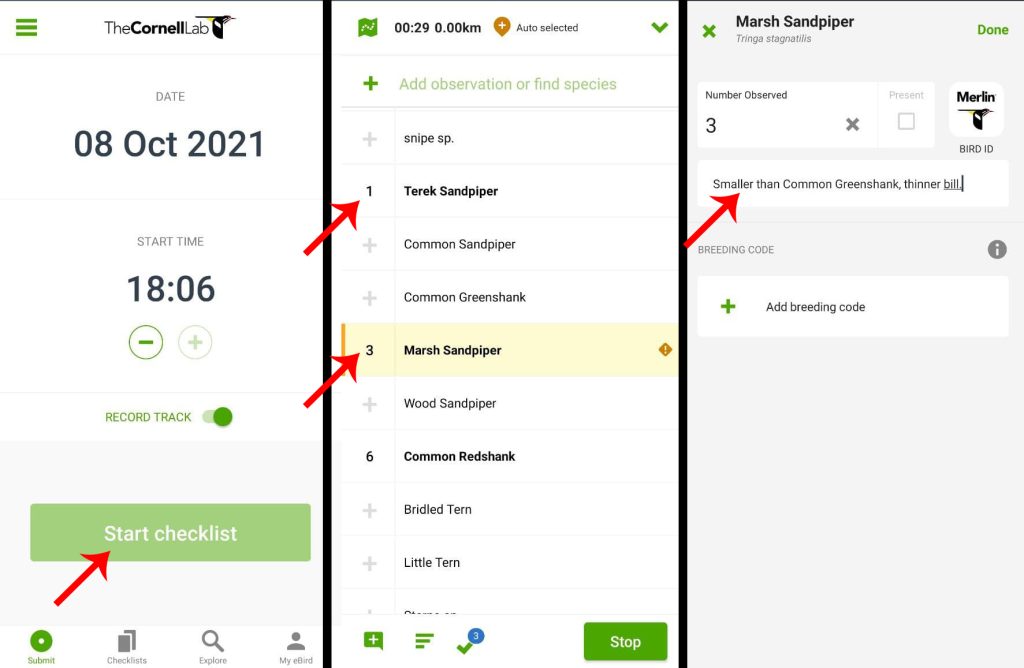

eBird is a citizen-science platform that was first launched over 10 years ago (Sullivan et al., 2009) and anybody is able to create an account for free. Through the platform, bird sighting information, along with their photographs and sound recordings, can be uploaded. A highly user-friendly mobile phone application is available and all you need to do when you are out birding is to start a list, select a location, and just tap a button that corresponds to a species you encounter in the field. Detailed information such as sex, behaviour, and other observations can be optionally added. A web platform is also available where you can later upload the photographs and sound recordings you took.

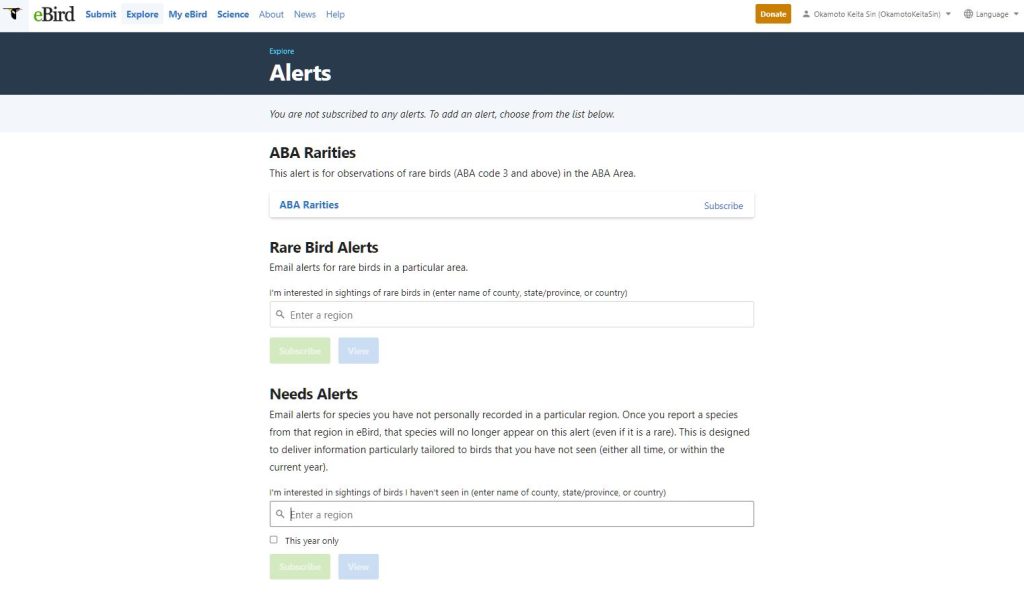

In your eBird account, not only will you be able to check your daily sightings, but you can also track your birding statistics by generating monthly or yearly summaries. Furthermore, there is a particular function that you would definitely love as a birder – the needs and rarities alert. These alerts will send you emails when other eBirders find a bird that you need (i.e. not recorded in your eBird account) or are locally significant. In these alerts, you can even set multiple filters to suit your needs: for example, if you have seen a Fairy Pitta Pitta nympha elsewhere before, you might not necessarily find the need to see one in Singapore so you can filter it out from your personalised eBird alert list. On the other hand, if you are doing a big year, you might want to search for relatively common birds such as the Dark-sided Flycatcher Muscicapa sibirica the moment one is locally seen.

Some might have reservations regarding immediate sharing of sightings – certain sites such as housing estates might be sensitive, or some birds might be nesting when you find them. In such cases, you can also upload your data post-hoc through an easily formattable excel sheet once you are comfortable with making the data public. Likewise, if you prefer to be private, there are options to upload your sightings anonymously or hide your lists (you will still need an account, but your name/list will not be displayed publicly). Additionally, concerns about the dangers of publicising locations for species such as the Critically Endangered Straw-headed Bulbul Pycnonotus zeylanicus due to the presence of poaching activities can be eased: there is a “sensitive species” filter set by regional reviewers that hides specific sites.

You might also be thinking: “I’m not a bird expert, what if I make mistakes?” – don’t worry! eBird data is constantly curated by regional reviewers that will ensure that the information is as accurate as possible. When potential mistakes are noticed, you will be notified via email. Moreover, when you are submitting data via the eBird application, the platform will flag out potential rarities that will allow you to enter specifics of your sightings. These filters are constantly reviewed and updated by the local expert (the eBird reviewer) to ensures that the flags do not appear irrelevantly. Uploading photographs and sound recordings will also be helpful, as not only is the reviewer able to check the data, any eBird user is able to report incorrect identifications. Similarly, you might be apprehensive about the perceived “quality” of the data you are contributing: “what if all the birds are common and boring? Won’t such data be useless?” – the answer is no! Data of all species – however common they are – are very valuable when conducting scientific research and consequently conservation planning. For example, if there is a site with 100 checklists per month, mostly filled with common species such as Yellow-vented Bulbuls P. goiavier and Brown-throated Sunbirds Anthreptes malacensis, we can be quite sure that conclusions we make based on information from the area is fairly accurate. Conversely, if checklists at such sites are not created because the species assemblage is “mundane”, the area will end up becoming a big question mark – could there be an undetected population of Greater Green Leafbirds Chloropsis sonnerati hiding there? Could there be huge numbers of introduced waxbills colonising the place? Furthermore, species that we think as “common” today might not continue to be in the future and vice versa. For example, the Red-wattled Lapwing Vanellus indicus, ubiquitous in most grassfields in Singapore today, was actually a locally rare bird just 20 years ago (Lok & Subaraj, 2009; Wang & Hails, 2007)! A steady stream of checklist will tremendously improve the data quality.

In Singapore, many of us share our sightings through social media sites such as Facebook groups or Telegram/WhatsApp groups; the eBird patronship fraction in our community is still relatively low. However, the number of eBirders has been rapidly picking up since ~2015, and the impacts of this increased usership have been tremendous. For example, Singapore’s first Siberian House Martin Delichon lagopodum and Hair-crested Drongo Dicrurus hottentottus were only discovered months after the birds were gone by A/P Frank Rheindt from the NUS Avian lab when he was scrolling through eBird photographs of the similar looking Asian House Martin Delichon dasypus and Crow-billed Drongo Dicrurus annectans. Similarly, counts from eBird were very useful in quantifying the sheer oddity of the 2019/2020 migration season we enjoyed two years back, especially for species including the Red-rumped Swallow Cecropis daurica and Whiskered Tern Chlidonias hybrida (Sin, Ng, & Kennewell, 2020). Data are not just restricted to members from the Cornell lab, but can be downloaded by any citizen-scientist or researcher upon request. These database, unlike information that are stored in notebooks, scattered pdfs, or people’s memory, are easily searchable and accessible. Both scientific and conservation action can be achieved with fine scale information, to which you can be a part of.

With all that said, I hope this article has broadened your perspective on how you can be an important contributor to bird science as well as improve the birding experience in our local scene!

Acknowledgements

A massive, massive thanks to Martin Kennewell (Singapore’s eBird reviewer) for the constant efforts in promoting the platform locally as well as taking on the tremendous task of moderating the data throughout the past few years. I also thank my team members from the Singapore Bird Project (Dillen, Francis, Movin, Raghav, Sandra), as well as Tan Hui Zhen and Geraldine Lee for comments on this article. Last but not least, a huge thanks to all eBird users out there, and if you are not one, I hope this article has convinced you to be one!

Disclaimer: Cornell is not paying me to write this article and I am also not presently involved in any research with them at the moment (I wish they did, and I wish I were!). I am an ardent eBird user and believe in the importance of data sharing and accurate data curation by the appropriate reviewer.

Literature cited

Sin, Y. C. K., Ng, D., & Kennewell, M. (2020). An unprecedented influx of vagrants into Malaysia and Singapore during the 2019–2020 winter period. BirdingASIA, 33, 142-147. Link: https://avianevonusdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/sin-et-al-2020_unprecedented-influx-of-vagrants-into-malaysia-and-singapore-2019-2020-1.pdf

Sullivan, B. L., Wood, C. L., Iliff, M. J., Bonney, R. E., Fink, D., & Kelling, S. (2009). eBird: A citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation, 142(10), 2282-2292. Link: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rick-Bonney/publication/248200195_eBird_A_citizen-based_bird_observation_network_in_the_biological_sciences/links/5747432808ae14040e28cf96/eBird-A-citizen-based-bird-observation-network-in-the-biological-sciences.pdf

Lok, A., & Subaraj, R. (2009). Lapwings (Charadriidae: Vanellinae) of Singapore. Nature in Singapore, 2, 125-134. Link: https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/app/uploads/2017/06/2009nis125-134.pdf

Wang, L. K., & Hails, C. J. (2007). An annotated checklist of the birds of Singapore. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology Supplement, 15, 1-179. Link: https://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/publications/raffles-bulletin-of-zoology/supplements/supplement-no-15/