Written by Keita Sin

Summary

- Various resources are available on our Birds of Singapore page (this website!). Information on our pages are curated via both our own birding experiences and through checking various references including field guides.

- Things to consider when choosing field guides include

- Geographical coverage

- Quality of identification details

- Presence/absence of range map

- Quality of species details

- Quality of plates/photos

- Accuracy of information

- Layout of field guide

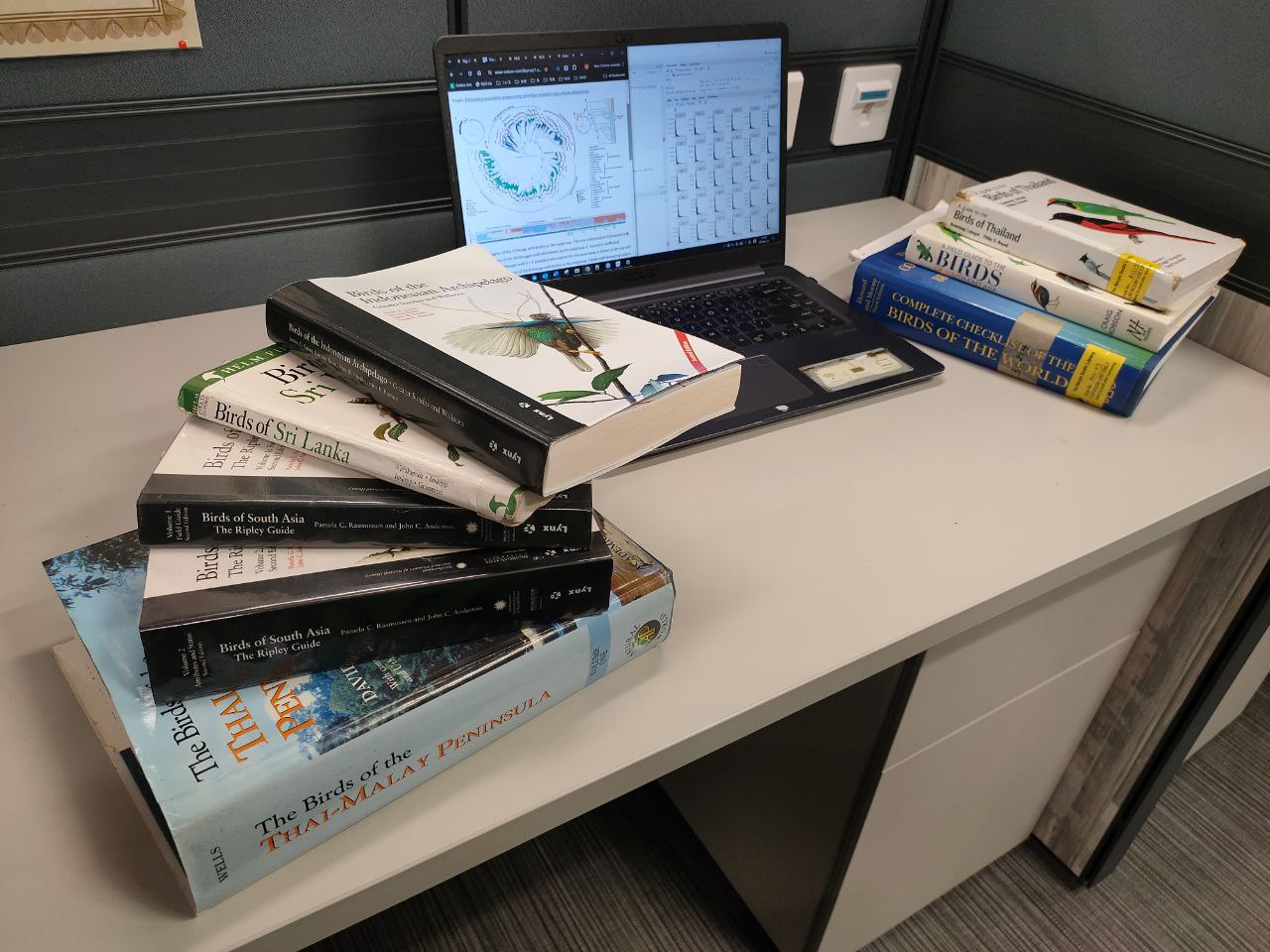

- We frequently refer to the following references for BirdSoc SG work:

- Field Guide to the Birds of Southeast Asia (2nd edition), by Craig Robson

- Birds of Malaysia, Covering Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysian Borneo and Singapore, by Chong Leong Puan, Geoffrey Davison, Kim Chye Lim.

- Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago, Greater Sundas and Wallacea (2nd edition), by James A. Eaton, Bas van Balen, Nick W. Brickle, Frank E. Rheindt.

At the Bird Society of Singapore, we are committed to providing the best online resource for birders from all levels of interest. Our Birds of Singapore page has tons of information:

- A detailed write-up for every single species of bird on our species checklist

- Multiple blog posts detailing how to distinguish difficult-to-identify species such as raptors, flycatchers, and more.

- Articles from different genres ranging from science, conservation, to birdwatching tips.

- Our carefully curated Singapore Bird Database that contains information on a select group of important species in the nation that we believe require proper documentation and archival.

- Recordings from some of our past talks!

While a large proportion of the information that we include in our website come from our own birding adventures, many of them are also from resources prepared by others; we stand on the shoulders of giants. We scour through peer-reviewed literature, grey literature (such as online checklists and blogs), as well as many books and field guides to ensure that the particulars we share are correct. While much literature can be found online today, the same cannot be said for field guides. Oftentimes they cost quite a fair bit of money, and purchasing one can be a huge commitment, especially for new birders and students. So here are some tips on how to pick the optimal field guide that gives you the most bang for your buck.

- Geographical coverage: Some field guides are written for a specific site (such as a national park) or country, while others cover a set of regions that are biogeographically related. Biogeography refers to the distribution of plants and animals across the world. For example, a hypothetical field guide on the birds of the country Indonesia will span across the biogeographic regions Sundaland, Lesser Sundas, and parts of New Guinea. On the flip side, another hypothetical field guide on the birds of the biogeographic region Greater Sundas will cover birds from the countries Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, and Thailand. In short, different field guides deal with different geographic scopes. If you foresee yourself repeatedly birding at that specific location only, then getting one with narrower scope might be sufficient. However, take note that such field guides typically will not include birds that might potentially arrive at the site as vagrants, and could be obsolete once you start birding just outside of the region. On the other hand, a regional field guide might contain many species and information that might be unnecessary in the specific location you are birding at, but will certainly be more useful if you foresee yourself travelling across the location for birdwatching. In Singapore’s context, we are located in Southeast Asia, and in the Sundaland region. Field guides that focus on this broad area will contain information on the rare birds that are here, and those that might potentially arrive in Singapore in the future. Regional field guides are also responsible for many birdwatchers’ wanderlust!

- Quality of identification details: Certain field guides provide excellent pointers on distinguishing features, while others simply describe the bird in a very general manner. Although both books definitely serve their purpose as a general guiding document for most species, the former will definitely trump the latter when dealing with the many similar looking birds you will encounter when birdwatching. Many times, these seemingly difficult birds are also the most exciting ones, so make sure you purchase the book that will give you what you need! A good way to assess the reliability of a field guide is by flipping through difficult to identify species such as raptors (sparrowhawks in particular), terns, waders, bitterns, flycatchers, and Phylloscopus and Acrocephalus warblers. These are the groups of birds that often throw off even experienced birdwatchers. If you only have enough budget to purchase one book, we recommend that you get the one that really puts in the effort to discuss the key identification pointers for such birds. For example, there might be books that use vague words such as “distinct” or “prominent” when describing species and features in complexes that are in fact very similar looking to each other. It might not be worth your money getting a book that uses the term “small and green” for multiple species of Phylloscopus warblers. Rather, you’d want to see the author’s efforts in describing the small key details. These efforts generally translate to other aspects of the field guide and you can be confident that the rest of the book is likely reliable as well.

- Presence/absence of range maps: For field guides that only focus on a relatively small and specific site, range maps might not be too important. However, for the majority of field guides around that cover a broad space, such maps might come in handy. These maps will not only help you save time by narrowing down the possible choices when identifying a bird in the field, they can also prevent you from misidentifying a bird you saw as something extremely rare/unexpected in the area. Unless you are already familiar with the birds covered, prioritising a field guide with these maps might be beneficial especially for regions that cover different biogeographic regions (e.g., the Malay Peninsula and Borneo in the case of Malaysia). This is especially because different regions can harbour different endemics, so having to read through the hundreds of texts to narrow down the expected species might not be a good use of time.

- Quality of species details: Some field guides go beyond the call of duty to discuss more than species identification. Details such as where and when a bird might most often be seen (e.g. Is the bird migratory? Is it endemic to a region? Does the bird like specific microhabitats? Will it be perched high or low?), behaviour (e.g. Does the bird tend to exhibit a specific feeding pattern or flight style?) and vocalisation (e.g. Is the bird usually loud or soft? Does it sound similar to another species?) are information that you should look out for. Additionally, quality of taxonomic notes, while seemingly daunting to some, is a good benchmark too. Certain subspecies of birds are known to be almost certainly distinct, but just have not been confirmed yet (e.g. Singapore could potentially have two different species of Black-naped Orioles). Knowing such details can enrich your birdwatching experience – you might otherwise regret not paying more attention to a bird during your overseas trip! For birds that have potentially overlapping subspecies (e.g. resident vs migratory subspecies that meet in winter), you should also watch out for whether the field guide lists the key distinguishing features of each subspecies.

- Quality of plates/photos: Plates generally refer to drawings prepared by artists, while photos will be pictures of the birds taken in the wild. Field guides that contain photos and plates have their pros and cons. Photographic field guides can be superb if the images are of high quality, and can often provide you an idea of what you might expect to see in the field (e.g. whether the bird will be on an open branch or in the undergrowth). However, it is important to check whether the birds are posed similarly, and whether the colour editing looks accurate. The reason why posing is important is because many similar birds in the world are often best distinguished by subtle structural differences that might otherwise not be reflected at certain angles (e.g. Lesser and Greater Green Leafbird in Singapore). Inaccurate white balance can also give the birds a very different impression. The accuracy of plates, just like photos, is highly dependent on the artist. However, while this might feel unintuitive to newcomers, well drawn plates are usually far more accurate than photographs in showcasing what the bird looks like. They will also be drawn at a similar plane to allow structural comparison and provides a relative scale of colour. In relation to this, another factor to look out for might be the wealth of photos/plates available for similar looking species. For example, some field guides have perched and flight views of raptors to provide an idea of what they would look like in different conditions. Others just “copy and paste” the same plate for similar looking species and tweak them slightly without paying attention to minute details. (Writer’s recommendation: while it might be a matter of preference, I would personally recommend getting field guides with illustrated plates).

- Accuracy of information: Details like the rarity of a species, taxonomy, migratory status are things that can change with time, and field guides will always be bounded to the details available when they are published. However, there are occasional field guides that contain multitudes of glaring errors even after considering these caveats. If you are purchasing a field guide to an area that you might not be familiar with, it could be difficult for you to assess whether such details provided in the book are accurate or not, but the last thing you’d want is to learn a bunch of wrong information. It will be a good idea to look up various online reviews (if there are multiple field guides for the area) or check with your more experienced birding friends to determine which the best pick is for yourself. Don’t always buy the latest book, sometimes the older field guides might be superior!

- Layout: several field guides have straightforward identification pointers and specific details of the species split up: all the plates and simple identification pointers are at the front section of the page, and the detailed write-ups are at the back. Others have these combined together. It’s largely a matter of preference, but if you are stuck between multiple field guides of similar quality, you might want to look into your preferred layout too.

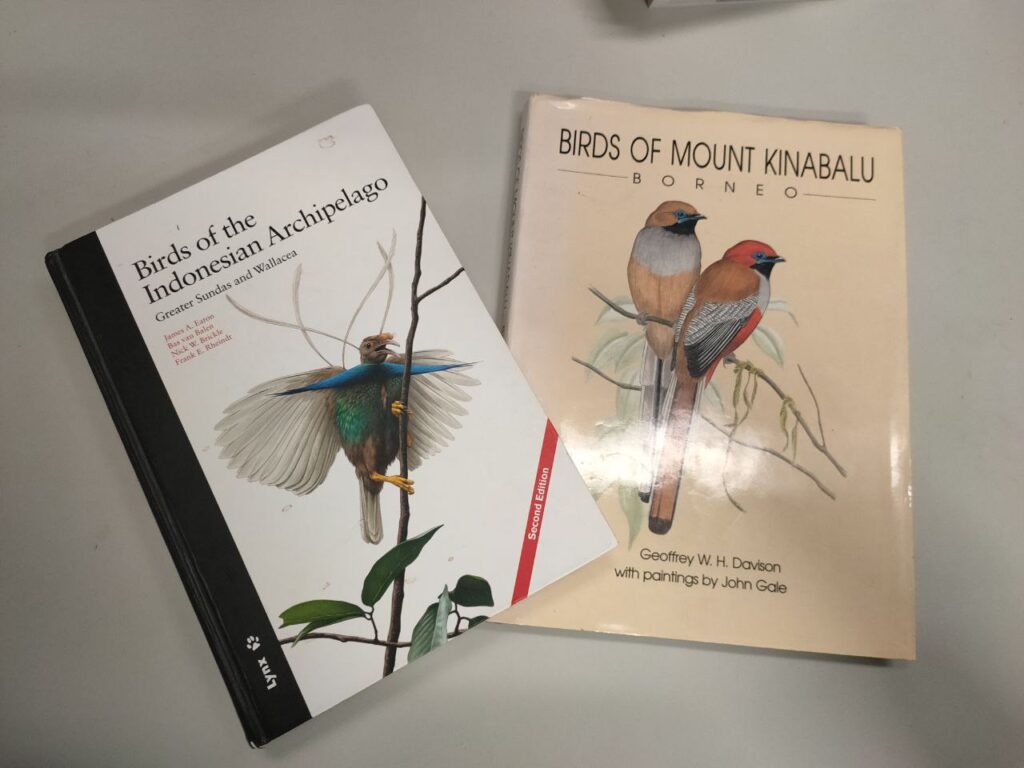

Different geographic coverages. Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago vs Birds of Mount Kinabalu (which is located in Borneo, and which species are also covered in the first field guide).

Photos vs plates (+ different geographic scope): Birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore (by Geoffrey Davison and Chew Yen Fook) vs Birds of South-east Asia, and their respective owl pages.

Field guides with different layouts and presence/absence of range maps: Chestnut-cheeked Starling in Birds of Southeast Asia vs Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago. Both field guides contain key identification pointers but differ in the presence/absence of range maps and layout. In the former, the detailed write-ups are split from the plates and the species ranges are spelled out. In the latter, information is combined and species ranges are in map format.

Field guides with high quality species details that are up to date: Black-naped Oriole in Birds of Malaysia, Covering Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysian Borneo and Singapore, with key identification pointers of the potentially distinct subspecies.

Other examples of useful species accounts

Additional pointers for consideration

Size and weight: This could come into consideration if you foresee yourself carrying your field guide around during your birdwatching trip (which we recommend if travelling in somewhere new). Typically, if birding with your friends, only one field guide is needed per group. Additionally, you could always leave your field guide at home/back in your accommodation and refer to it at night by counter-checking with your field notes or photographs. There are various online resources that can serve as quick alternatives for field guides outdoors too, such as the Birds of Singapore website!

Hardcover vs flexicover: Some field guides offer a selection between these two. It’s ultimately up to your preference, but for extra water protection, keeping your field guide in a waterproof/ziplock bag can help protect your precious resource from damage.

So, which field guide do we usually use?

The tips above should provide you a good start for searching for your first field guide. Many of us who curate the Bird Society of Singapore resources have had the opportunity to read many of the field guides around, and here are some of the resources that we frequently refer to when curating our website and research work.

Field Guide to the Birds of Southeast Asia (2nd edition), by Craig Robson. The first edition of this field guide was published in 2000, and the updated second edition in 2008. This field guide covers the countries in continental Southeast Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, Peninsular Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia) and hence has all the birds that occur in Singapore (except the very unexpected birds like Spotted Flycatcher that turned up in recent years) as well as many other potential birds that might come here (e.g. the Two-barred Warbler that recently showed up!).

Birds of the Indonesian Archipelago, Greater Sundas and Wallacea (2nd edition), by James A. Eaton, Bas van Balen, Nick W. Brickle, Frank E. Rheindt. The first edition of this field guide was published in 2016, and the updated second edition in 2021. This field guide covers the Indonesian Archipelago (the Sundaic islands of Sumatra, Borneo, Java, plus the thousands of islands that spread across Indonesia) and technically does not contain Singapore within its focal range. However, since Singapore is biogeographically pretty much the same as the Sundaic islands covered, practically every single species in the nation is covered in the field guide as well. The few examples of birds not covered are vagrants such as the Chinese Blue Flycatcher and Daurian Redstart. Funnily enough, Two-barred Warbler is included in the book since it showed up in Sumatra before it did here! This book also provides a rough idea of potential birds from the region that might show up in Singapore (e.g. Pied Stilt, which is not in the field guide above, has already arrived and bred locally in Singapore).

Birds of Malaysia, Covering Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysian Borneo and Singapore, by Chong Leong Puan, Geoffrey Davison, Kim Chye Lim. This field guide was published in 2020 and the title says it all. This field guide contains the latest insights that were available as of 2020, and we often consult it when sourcing information of birds in the region.

There are two additional resources that we often refer to, which are Volumes 1 and 2 of the Birds of Thai-Malay Peninsula by David Wells. These books, which cover non-passerines and passerines respectively, are not meant for the field. Despite being slightly old, they contain a shockingly detailed wealth of information that no newer book can compete with and are so thick that they could probably save your life during a gunfight. We would only recommend considering these books if you are serious about “nerding out” on the birds in our region at home. There are even other books focusing on certain families of birds! Books like Pipits and Wagtails of Europe, Asia and North America: Identification and Systematics by Per Alström and Krister Mild have been very useful in our BirdSoc SG work.

We hope these pointers will be useful for you in choosing your field guide. And of course, if you ever need information about Singapore’s birds, remember to refer to our excellent website first!

Disclaimer: Neither BirdSoc SG nor the writer of this article is receiving any form of commission or favours from the field guide authors/publishers. My intention is not to promote these books. Rather, we really do rely on these resources for both our professional work and birdwatching expeditions. Additionally, I made a deliberate choice only to feature “good” examples rather than comparing them against what some might think of as an “inferior” field guide. The intention here is not to criticise any work.