Written by Richard White

There have been a number of articles about birding in Singapore. As times change, so does the Singapore birdwatching/birding/bird photography scene. Once in a while it’s worth taking a few minutes to take stock of where we are at, how we got here and where we might be going.

This article is not intended to be serious. It’s not an in depth look at the socio-economic drivers behind our hobby. It’s not going to investigate the growth of the hobby during the travel restricted days of Covid-19. I’m not going to do a detailed analysis of the impact of social media and messaging forums as a means of disseminating bird news.

I’m primarily interested in listing. Most people who spend time in search of birds have a life list of some description. I’ve met people who claim they do not. I doubt that these claims would stand up to rigorous scrutiny. Even those who don’t have an actual number in mind, know what they have and, perhaps almost more importantly, have not seen.

For some it is the foundation of the hobby – the urge to collect, to add one more to the list. And here I want to make a very important point. There’s no judgement here. It’s your hobby. It’s supposed to be fun. And when it comes to your list, it’s exactly that. Yours. Your list, your rules. You count whatever you want. Don’t come at me because you disagree with something here.

At the time of writing there are 429 species on the Singapore list. There was a time when a Singapore list of 350 seemed an almost unattainable goal. Now there are probably in excess of 20 Singapore birders who have passed that tally, and several have broken the 400 mark.

There are a couple of quick and easy explanations for this. Firstly, longevity of individual birders. There are now birders who have been on the scene in excess of 20 years, many who have been around a decade or more. It’s hardly surprising that the longer you spend birding, the more you will see. And the Singapore list has grown over time. The list broke the 350 barrier in 2013, so again it’s no surprise that a decade ago a list of 350 seemed unattainable.

Where have all these “new” birds on the list come from?

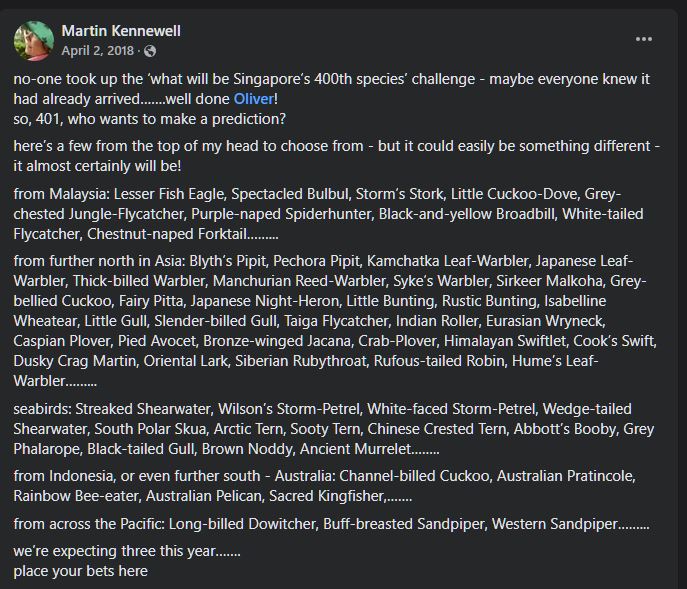

As the Singapore list passed 400 in 2020 Martin Kennewell (we miss you Martin!) challenged Singapore birders to predict the next new species for the list. At the same time, he posted some of his predictions – 60 species in total. Of those 60, two (maybe three) have occurred (Fairy Pitta, Taiga Flycatcher (and Wilson’s storm-petrel which was considered unproven)). So there have been 26 species that did not make it onto his list.

Looking through those species there’s no simple answer about where to look for the origins of the next first. It could just as easily be a wanderer from lowland Sundaic forests as a long-distance migrant.

And there’s no simple answer about where to search in Singapore. Anywhere from under-watched sections of Telok Blangah Hill Park to random park connectors in Clementi. Yes, places like Jelutong Tower and Kranji Marshes area have a great track record, but this is as much to do with regular coverage from dedicated birders as anything else. Your chances of finding something are likely as much to do with how much time you spend in the field as much as where.

At the same time as the scale of life lists has changed, so has the concept of a year list. Seeing as many species as possible in a single calendar year will always be a remarkable test of endurance, and ten years ago anything over 250 species was considered to be a really good effort. Recently, the 300 barrier has been broken more than once.

Here we see something different going on to the increasing Singapore life list. Year listing is not about longevity. It doesn’t matter how many years you have been birding (and notably some recent high achievers in the year list stakes have been relative newcomers to the birding scene).

There are some simple numbers to play with here. In 2024 the Singapore list is 429, so seeing 310 species in a year is 72% of the total. Back in 2013 a year list total of 252 represents 72% of the total Singapore list at that time. I know – not exactly comparable but there’s something here.

What else has changed?

It’s fair to say that the size of the community has grown. More observers in the field means more eyes searching which should mean more records. And as the community has grown, so has the experience and knowledge within the community.

The status of several species has changed significantly in the past decade so that former rarities are now more or less expected annual migrants. This could be down to environmental changes that have influenced population size or migration routes. But in other cases, such as Sakhalin Leaf Warbler, it is likely a result of more experienced observers. The first record of the species in Singapore was as recent as 2013, but it is now detected annually in Singapore. The species has a distinctive high pitched call, which is now known by many more local observers than a decade ago.

The equipment carried has also changed. Primarily, and most importantly, the quality of cameras has improved massively. More megapixels on the sensor and the ability to shoot at a higher ISO means longer lenses. Distant dots in the sky are now being resolved as rare raptors which would formerly have passed by unseen or unidentified. And one can only wonder about the change in the status of White-throated Needletail. The second record of this species for Singapore was as recent as 2017 (thanks Keita!), the most recent update to the database lists 39 records. Was this species overlooked before 2017 as high-flying speeding projectile needletails were either unidentified or passed off as more common species?

And there’s no doubt that messaging apps have changed the way in which news of unusual sightings is shared. At the time of writing, a single bird information chat group on Telegram has 2928 users. Not only is the news of the presence of a bird shared, but the identification can be checked and verified. And the use of a GPS enabled smartphone also means that the location of the sighting can be shared with precision.

This is all increasing the chances of seeing more species. There’s a downside too. The well documented decline of shorebirds on the East Asian – Australasian Flyway will likely continue. Certain shorebirds are going to become tougher to find. Already birds like Long-toed Stint and Grey-tailed Tattler are harder to find than a decade ago. The last accessible tattler record was from Pulau Ubin in 2019, Sungei Buloh has not had a record since 2016.

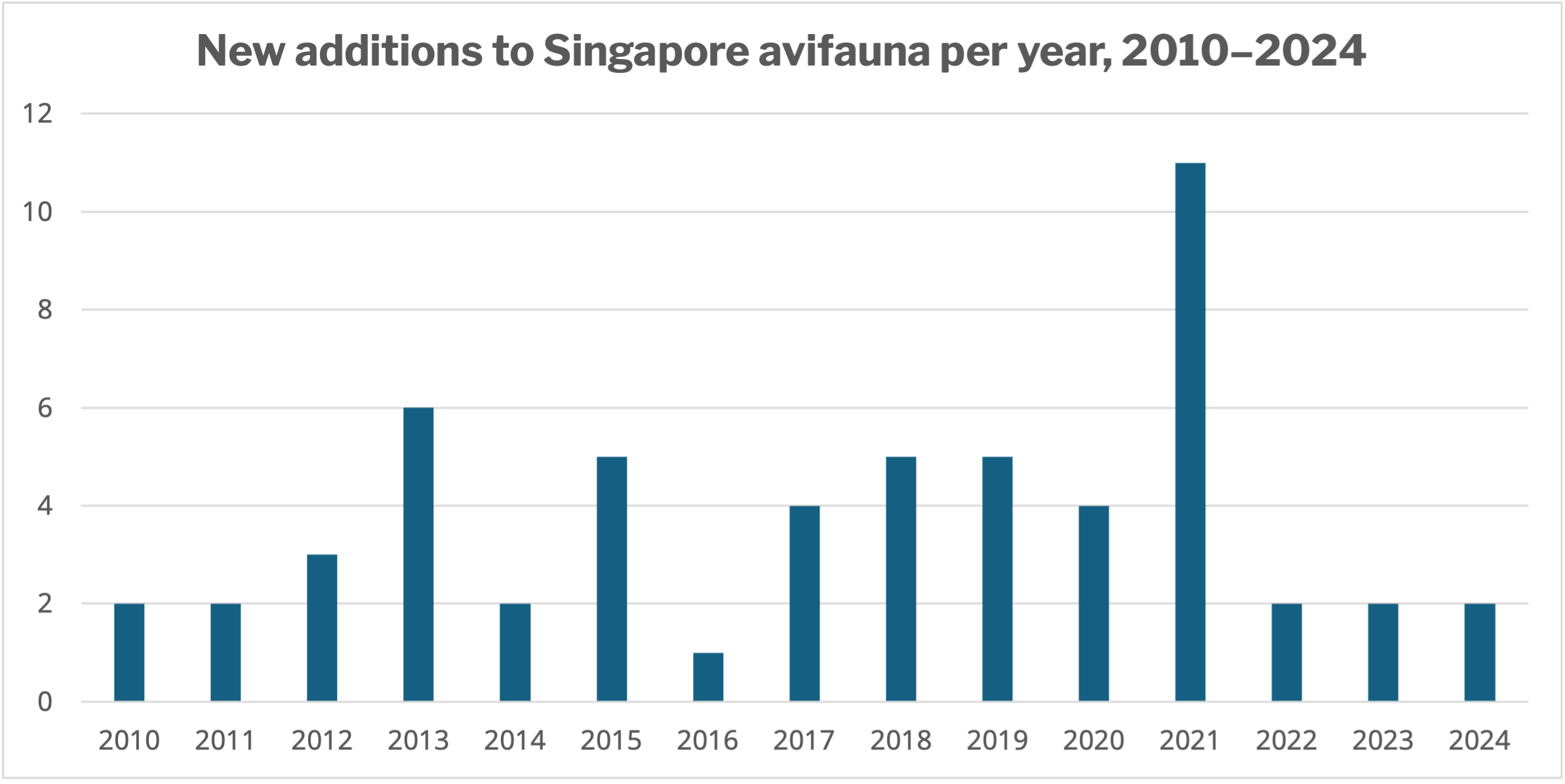

Where are we going? I’d be prepared to suggest that the rapid pace of change seen in the hobby in the past decade will slow down. That the Singapore list will continue to increase – maybe 2 to 4 species per year. The 11 new species recorded in 2021 will forever live in the memory of those fortunate enough to experience it as freakishly good year. More birders will reach the heady heights of 400 on their Singapore list. More birders will enjoy/endure the challenge of seeing 300 species in Singapore in a year. A few more cryptic, overlooked, species will emerge and we’ll enjoy the challenge of learning how and where to find them.

Mainly, I hope that more people will enjoy the “crippling addiction” (Yip Jen Wei pers. comm.) of this hobby.

Correction: With the recent addition of the Black Stork, the Singapore Bird List is now 429 and not 428.