Written by Yip Jen Wei and Sin Yong Chee Keita

Editing by Tan Hui Zhen, infographic by Kee Jing Ying

In the winter migration season of 2021/22, our community was graced by five appearances of Himalayan Vultures Gyps himalayensis. These massive birds are rare but increasingly annual migrants to Singapore and never fail to spark huge hunts for a chance to see them perched or to witness their incredible wingspan in flight.

No other species seems to unite the entire community in a truly islandwide effort as much as a flock of Himalayan Vultures slowly soaring across the island. Their size and slow flight means that regardless of where you are at the time of sighting, if they pass by your general vicinity, there is a chance you will get to see them.

Here are the accepted records of Himalayan Griffons the 2021/2022 season, as per the Singapore Birds Database:

Sighting 1: 8 Dec 2021

-

- Flyby of a single bird over Dairy Farm Nature Park, by Feroz and KW Seah.

- Most likely the same bird seen flying by over Singapore Botanic Gardens that evening, by Marcel Finlay.

Sighting 2: 27 and 28 Dec 2021 (Novena flock)

-

- Five birds soaring over Novena in the evening, by Wong Weng Fai.

- Almost certainly the same five birds seen again the next morning at the same site and across Singapore.

Sighting 3: 29 and 30 Dec 2021 (SBG flock)

-

- Five birds at Singapore Botanic Gardens (possibly the same five?), along with Singapore’s first Cinereous Vulture Aegypius monachus seen by perhaps over 300 birdwatchers across two days before taking off on the morning of the 30th.

Sighting 4: 12 and 13 Jan 2022 (Punggol pair)

-

- Two birds seen soaring over Punggol by Daryl Tan, with one bird later observed being mobbed by crows at Pasir Ris by Emily Koh.

- The next day, one bird – likely one of the two seen the previous day – at Pasir Ris Park by multiple observers.

Sighting 5: 18 to 19 Jan 2022 (Bukit Batok flock)

-

- Seven birds seen over East Coast Park by Rachit in the afternoon, last seen roosting at Bukit Batok Nature Park by Francis Yap and JJ Brinkman. All 7 birds were seen flying off the next day.

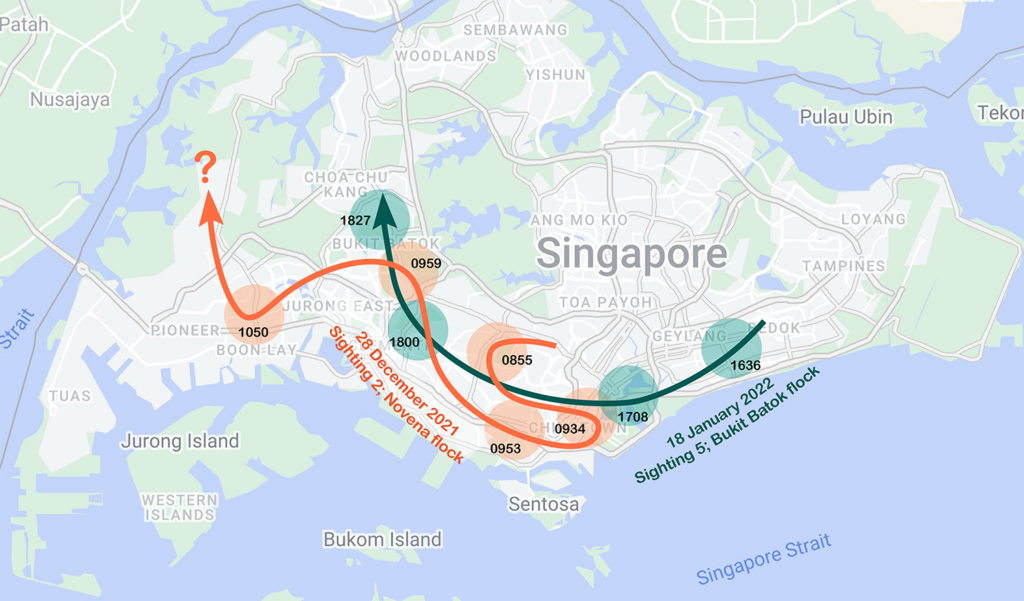

The very unique result of all the excitement surrounding Himalayan Vulture sightings is that every aspect of their presence—how many of them, their behaviour, their flight path—is quite well tracked. Combine that with Singapore’s tiny country size and the recent massive increase in community size, we have an extremely high observer density: the movement of the birds across the island were particularly well-documented on 28th Dec 2021 (Novena flock) and 18 Dec 2022 (Bukit Batok flock). The Bukit Batok flock also allowed many who could not pop their heads out of the window during work to look for them later that evening and the next morning.

Annotated flight paths of sightings 2 and 5 starting from Novena and Bukit Batok respectively, recreated based on the collective information shared by birders of Singapore through various social media groups.

All sightings from this season were of immature birds, as are most records from the region. Young birds are typically known to wander around more so than adults, and in the cases for the birds that end up in Singapore, quite far off course from where they would usually be. Records show that there’s an increasing trend in their numbers arriving over the years too. Of course, we have to be careful about extrapolating too many conclusions from this: as the number of birdwatchers go up, so do the number of rare sightings, but could other factors have contributed to their increased sightings in Singapore? Climate and land use change are speculated to have increased their occurrence in the region over the past few decades. Additionally, a vulture restaurant has been set up in Phuket since 2019. Could this have allowed some birds to accumulate enough energy to make it further south than previously possible? There have been talks on introducing such a system in Singapore too—how could this potentially help or affect the birds? There are many more questions than answers for now, much of it requiring research and discussions beyond the scope of this article.

Another slightly easier question that comes to mind is: were this season’s sightings of the same flock flying around, or new birds arriving each time? Those birds that were seen on two consecutive days at sites they were known to roost are quite surely the same individuals, but what can we make of the separate sightings? We could attempt to answer this question by examining some photographs taken across the sightings.

As seen from the images, many of the birds have rather worn wings and tail feathers, making it quite difficult to ascertain individuals. However two birds did have comparatively “unique” wear.

Interestingly, it appears that one individual from the Novena flock photographed on 28 Dec 2021 had several matching features of wear and tear of plumage. This is strongly suggestive that at least one (if not all) of the 5 Vultures from the Novena flock reappeared in the SBG flock along with the Cinereous vulture. The case is even more compelling when we note that both sightings had 5 Vultures: perhaps the same flock left Singapore on the 28th at 1300h, only to return on the evening of the 29th at SBG?

Then we notice that one bird from the Novena flock with a somewhat unique missing secondary (giving it a very “long-looking” tear) could (??) have participated in the Bukit Batok flock.. If the two photographs taken were indeed of the same bird, it suggests that the bird could have hung around the region and returned to Singapore after three full weeks! As always, it is important to keep in mind that plumage wear is common in long distance migrants and that this singular feature is suggestive but not indicative.

It goes without saying that many of the above deductions are based on guesswork, but exercises like this could bring us one step further to learning more about their behaviour in Singapore. When the vultures next arrive, taking ample photographs of them from multiple angles, will help to pin-point traits unique to individuals (if any) to help us estimate how long the birds typically stay around for.

Using plumage wear to identify individual birds is helpful in determining the number of otherwise rare migrants. The same technique was applied on an interesting case study this season elsewhere: we are quite confident that there were two Common Kestrels on the same day at Seletar Aerospace Drive. On 14 Dec 2022, one bird with strongly marked underwing coverts was photographed there by Lim Ser Chai. The next day, this species was seen again by Woo Jia Wei twice, but once at 1340h involving a bird with faintly marked underwings and broken primaries, and later at 1500h a bird that looked like the previous day’s individual!

Finally, the question that we all hope to know the answer to: what’s the best strategy to search for them again next season?

Five sightings is far from a good sample size, but the observations from this season might provide hints when searching for them again. First, if the birds are seen soaring late in the afternoon, chances are that you might be able to head down to observe them later in the evening or the next morning if they roost somewhere visible. These birds seem to have a tendency to remain in Singapore island overnight when detected later in the day. Given their massive size, they are highly reliant on thermals (rising hot air) to engage in soaring flight, making water bodies a possible deterrence for them. Perhaps this could be part of why the seven birds from the Bukit Batok flock chose to fly along the coast rather than further south to Bintan/Batam? For those aiming for flight shots, their take-off time is also likely highly dependent on the weather, though typically not too early in the morning. The Novena flock took flight around 0900h, the SBG ones around 1020h, and the Bukit Batok flock, around 1145h. Again the presence of thermals is essential for their flight, though where they might head off afterwards remains unknown to us for now.

Becoming the first person to find the vultures requires a little more serendipity. Initial sightings of Vultures are fairly unpredictable and highly dependent on being at the right time at the right place. However, knowing when to pay attention helps: previously, scarce sightings were from late December and January, but the 8 Dec 2021 proved a new early date, and no birds were detected past January despite the many occurences. For now, December to January seems to be the prime time to keep our eyes glued to the skies, and you can refer to the bar charts from our Singapore Bird Database for more information on when to look for them (and other rarities too!)

As the summer months approach, it is quite unlikely that we will see any more vultures before next season (but who knows!?). We’re approaching the season to search for possible Austral migrants and dispersals from Malaysia, but come December some of these birds might head here again. With so many pairs of keen eyes and quick cameras around nowadays, it has become easier than ever to track the habits of these vultures. The small bits of information we are able to piece together through social media may not seem like much, but as we repeat the process year after year, new insights into the birds’ habits may reveal themselves. It doesn’t take much to help: just share your sightings and submit your record to our database!

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Con Foley, Daryl Tan, Feroz, Herman Phua, Jared Tan, Justin Jing Liang, Lim Ser Chai, Marcel Finlay, Martin Kennewell, Siew Mun, Trevor Teo, Wee Aik Kiat, Wong Weng Fai and Woo Jia Wei for sharing excellent images of the birds. We also thank the community for sharing the sightings very promptly, allowing everyone to get exciting views of the birds. Last but not least we thank the Singapore Birds Project team for comments on this article.

References

Praveen, J., Nameer, P.O., Karuthedathu, D., Ramaiah, C., Balakrishnan, B., Rao, K. M., Shurpali, S., Puttaswamaiah, R., & Tavcar, I. (2014). On the vagrancy of the Himalayan Vulture Gyps himalayensis to southern India. Indian BIRDS, 9(1), 19-22. pdf

Yong, D. L., & Kasorndorkbua, C. (2008). The status of the Himalayan Griffon Gyps himalayensis in South-east Asia. Forktail, 24, 57-62. pdf and associated erratum

Errata

18 May 2022: We previously mislabelled the dates for the Pasir Ris Park and Bukit Batok Himalayan Vulture photos, the map, and the first Common Kestrel photo.