Written by Richard White, infographic by Keita Sin

Editing by Martin Kennewell, Keita Sin, Sandra Chia, & Dillen Ng

The birding community was presented with an identification challenge today with the arrival of a vagrant pipit species. These small, brown, streaky birds can be difficult to identify at the best of times. An unfamiliar, out of context, vagrant can be a real headache. So how to start the identification process? These notes might help.

Worldwide, there are about 40 species of pipit, mostly in the genus Anthus. Within Southeast Asia nine species are regular; in Singapore Paddyfield Pipit A. rufulus is a resident breeder, Red-throated Pipit A. cervinus is an annual non-breeding visitor in small numbers and Olive-backed Pipit A. hodgsoni is a rare vagrant with only one record at Bidadari in December 2010.

A bird discovered in a small suburban park in Clementi, Singapore, on 23 October 2021 by Soh Kok Choong was initially misidentified as a Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis. This species is a rare vagrant to Singapore with one previous record at Pandan Reservoir in November 2018. Jan Jaap Brinkman saw the post on 25 October, realized it was not a Eurasian Skylark but more likely to be a Tree Pipit A. trivialis (a first record for Singapore), and alerted the birding community. It was relocated quickly on 25 October and the identification of Tree Pipit confirmed.

But how do we know it is a Tree Pipit? Ideally, it would have been heard to call. While pipits tend to look alike (variations on brown and streaky), their calls are helpful and in most cases distinctive. Calls are notoriously hard to describe, which is why I am going to direct you to resources such as Xeno-canto should you wish to learn more about pipit calls. Unfortunately, this bird was either silent or could not be heard to call over the traffic on Clementi Road.

Faced with a silent pipit, how do we make an identification? First, let’s discount the commoner options (without spending time here on why it is not a Eurasian Skylark).

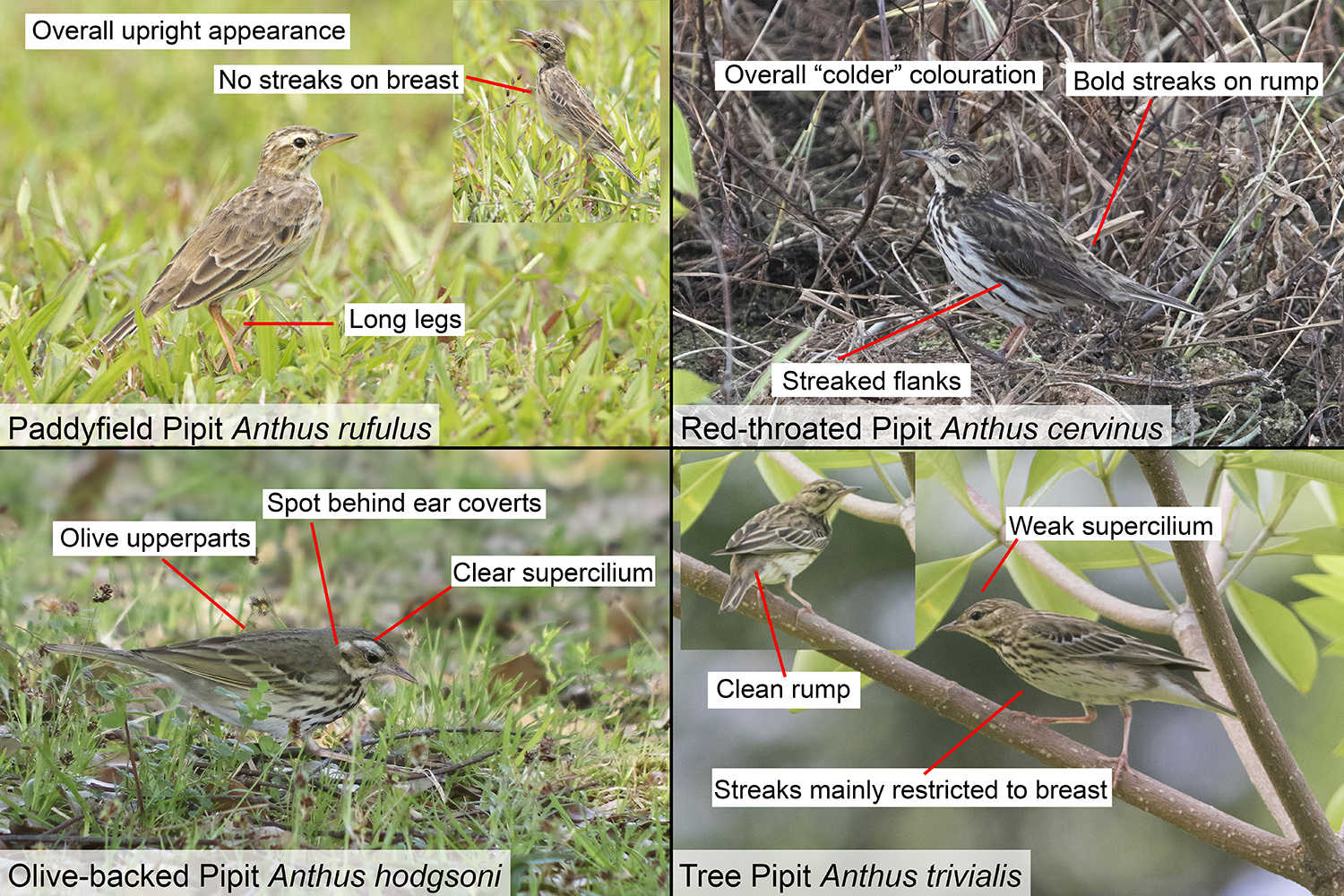

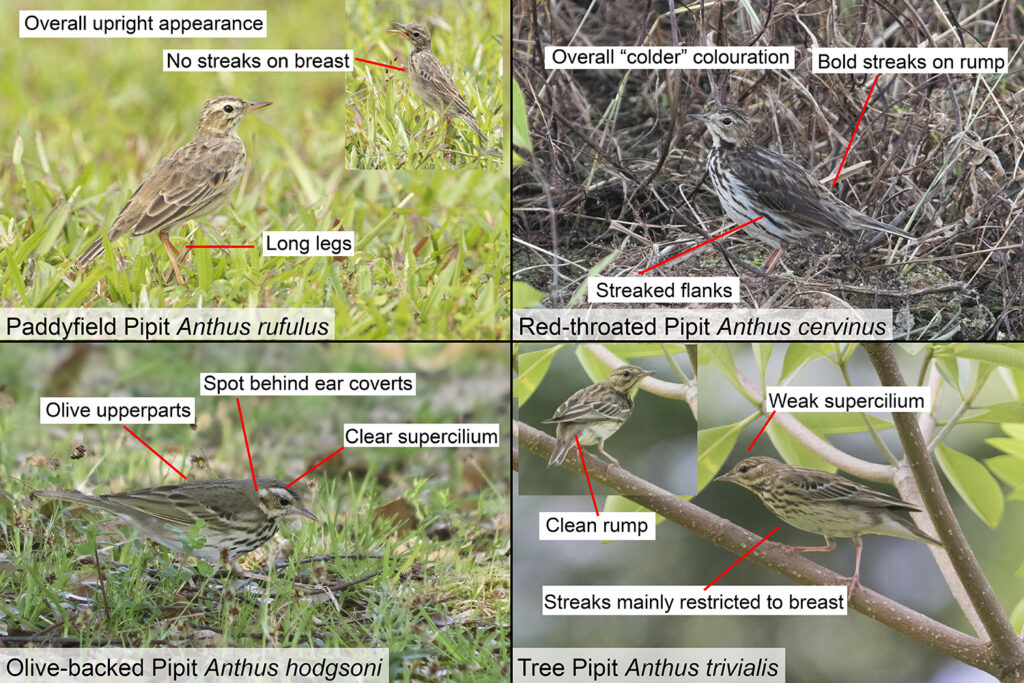

Of the three pipit species previously recorded in Singapore, Paddyfield Pipit is the commonest and therefore most likely pipit to be encountered. It is one of the larger pipits, >16 cm long and has a longer-legged and more upright appearance than the other pipits which are smaller and more horizontal in their stance. Size has to be used carefully, since the smaller pipit are merely < 16 cm long. Without being very familiar with pipits, this marginal size difference in a lone vagrant individual may not be helpful. The other feature that points away from Paddyfield Pipit is the extensive streaking across the breast of this bird, more than would be found on a Paddyfield Pipit. This combined with the short-legged, more horizontal gait, indicate that this pipit is not a Paddyfield.

Red-throated Pipit is the next most likely option. Smaller, with a more horizontal gait, this species is similar to a Tree Pipit in non-breeding plumage. However, the streaking on the breast typically extends strongly onto the flanks which this bird does not have. The upperparts are usually more boldly streaked to the rump as well, again lacking in this bird. Red-throated Pipit also typically has strong off-white mantle braces. These pale lines can be seen on this bird, but are not as well marked as would be expected on a Red-throated Pipit. The plumage tones of this bird give an impression of warm buff/browns in tone, while Red-throated Pipit should be colder grey/browns. So it appears the bird is not a Red-throated Pipit and therefore a real rarity.

Olive-backed Pipit is the only other pipit species to be recorded in Singapore. As the name suggests, the upperparts of this species should give an impression of olive/brown, which is not seen on this individual. Olive-backed Pipit typically also shows a strongly marked head and face pattern, with a clear supercilium above the eye and a well marked spot at the rear of the ear coverts. Lacking these features, this bird is not an Olive-backed Pipit either.

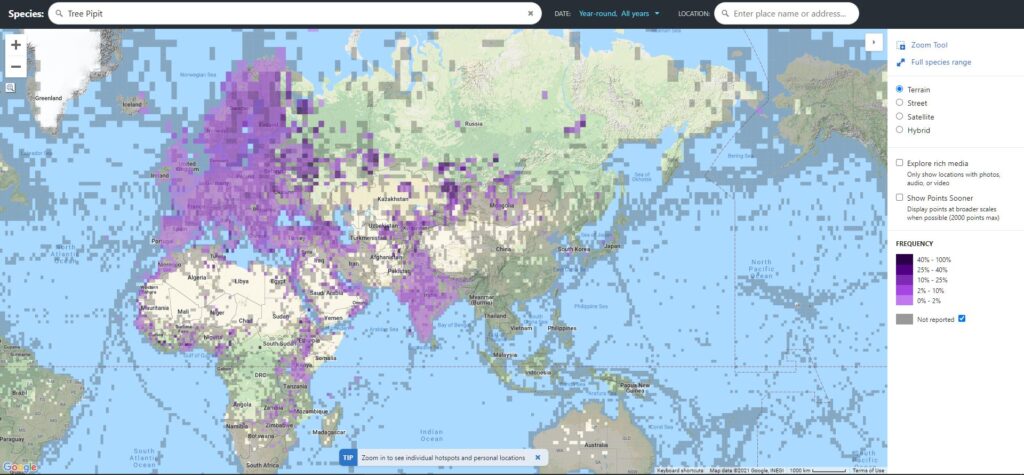

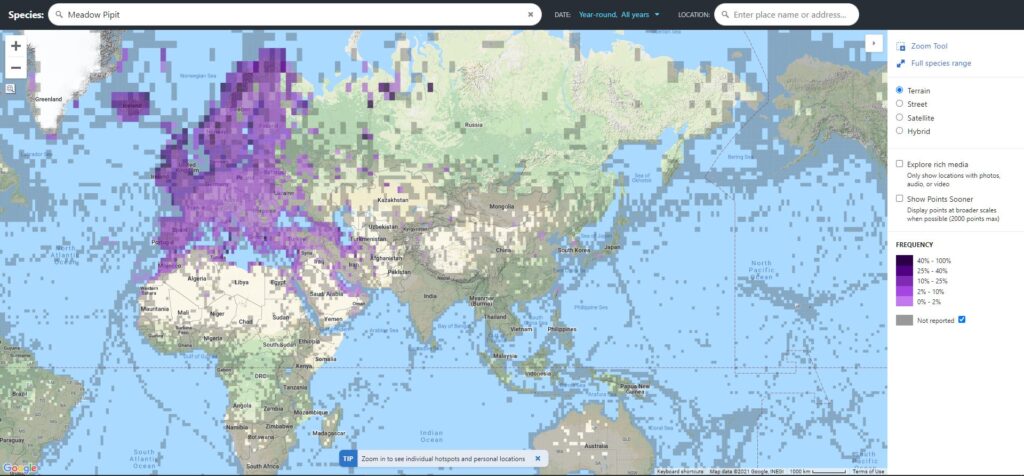

Now into the territory of a national first, the list of possibilities opens up. Within the region, Rosy Pipit A. roseatus would be more boldly marked, and Buff-bellied Pipit A. japonicus lacks the warm plumage tones of this bird. It is not one of the larger pipits (Richard’s A. richardii, Blyth’s A. blythi or Long-billed A. similis). We are left with Tree Pipit or maybe something even more extreme from outwith the region, such as a Pechora Pipit A. gustavi or Meadow Pipit A. pratensis.

Pechora Pipit is easily discounted since it shows a distinct primary projection beyond the longest tertial, which this bird does not show.

Meadow Pipit, typically a short distance migrant, is an outside chance from much further west. Though this makes it less expected, it should be considered. It is superfically very similar to Tree Pipit, but typically shows a clustered spot of streaking in the centre of the breast not shown by this bird. It is also less likely to perch in trees as this bird did often. The call is different but this silent bird does not help us. Finally and conclusively, scrutiny of digital images shows this bird has a short hind claw – shorter than would be seen on a Meadow Pipit.

Our lone, silent, pipit can be confidently identified as a Tree Pipit based on the plumage and structural features, as well as the behaviour and gait (jizz):

- Underparts: Well marked narrow black streaks across the chest/breast on a warm buff base. Streaks do not extend strongly onto the flanks

- Upperparts: warm buff/brown, with dark centred feathers giving a well marked, but not strongly contrasting, appearance. A well marked row of median primary coverts were slightly darker centred and paler fringed than surrounding feathers, producing a clear (but not bold) wing bar.

- General behaviour: spent most time walking through long grass foraging for invertebrates with a horizontal gait and occasionally giving gentle tail pumps (which is also a feature of Olive-backed Pipit). Flew with a strong bounding flight into mid-canopy of trees where it would perch, rest and preen before returning to feeding on the ground.

Further notes:

1) Edited 26 October 2021: The upperparts description previously read “A well marked row of greater primary coverts … …”. This has been corrected to “row of median primary coverts … …”.

2) After the release of our article, Siti Soedarsono shared with us that she photographed the bird earlier at the same site on 19 October 2021. This date serves as the new first date for this record. We thank Siti for graciously sharing the information.