Raghav Narayanswamy

Introduction

Since Singapore’s first confirmed occurrence of an Oriental Turtle Dove Streptopelia orientalis in 2018, there have been three subsequent records of two distinct individuals in 2023 and 2024 respectively. The species is currently included in the Singapore Bird Checklist as a vagrant, based on the assessment of the initial record by Sin & Ng (2021). The latest record at Labrador Park prompted the Singapore Bird Records Committee (SBRC) to review all past Oriental Turtle Dove records in Singapore to clarify the species’s status in the face of new evidence. We present our results here.

Background

There have been four records of this species in Singapore, two of which are related to the same bird, as listed in the table below.

| Date (number of individuals) | Location | Remarks |

| 28 Nov 2018 (1) | Sisters’ Islands | |

| 8 Jan 2023 (1) and 4 Feb 2023 (1) | Rower’s Bay Park and Lim Chu Kang Lane 3 | Two records of the same bird |

| 27–30 Jan 2024 (1) | Labrador Park |

Of the five subspecies of Oriental Turtle Dove, two are partially migratory, with the northern populations of subspecies meena and orientalis migrating south during the winter; this table lists all the subspecies, based on IOC 14.1:

| Taxon | Range | Notes |

| Streptopelia orientalis orientalis | Central Siberia to Japan, China, the eastern Himalayas and Taiwan; northern populations wintering to central Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam | Migratory, with vagrants recorded in Europe (but see below). |

| S. o. meena | Southwest Siberia to Iran and the central Himalayas; wintering in rest of Indian Subcontinent | Migratory, with vagrants recorded in Europe and Middle East (but see below). This subspecies is sometimes referred to as “Rufous Turtle Dove”. |

| S. o. stimpsoni | Ryukyu Islands (Japan) | Unlikely to occur in Singapore given its highly sedentary nature. Not distinguishable from orientalis in the field. |

| S. o. erythrocephala | Central and southern India | Unlikely to occur in Singapore given its highly sedentary nature. |

| S. o. agricola | Northeast India, Myanmar and northern Thailand to south-central China | Unlikely to occur in Singapore given its highly sedentary nature. |

Like many Asian migrants, vagrancy to Europe is established. A feral population of subspecies orientalis in Czechia which originated from a large release of captive birds may, however, throw doubt on some recent records of that taxon in western Europe (Berka & Horal, 2023). There are several records from the United Kingdom, the vast majority of which are juvenile or subadult birds (Naylor, 2024).

Ship assistance is a phenomenon widely known to occur in birds but is poorly characterised, and little information is available on the spatial characteristics and species breakdown of ship-assisted birds in the region. It is likely quite frequent for many migratory birds to take short breaks on ships before they arrive in their wintering grounds, including species that are regularly recorded as migrants in Singapore, like the Brown Shrike Lanius cristatus and Eastern Yellow Wagtail Motacilla tschutschensis in this Facebook post. We specifically examined the ship-assistance potential in the Oriental Turtle Dove, as discussed here and in the Assessment section.

There are also several records of the Oriental Turtle Dove in North America, many of which are believed to be ship-assisted birds (Howell et al., 2014). These are discussed more extensively in the Assessment.

One record from Cocos (Keeling) Islands in March 2014 was accepted by the BirdLife Australia Rarities Committee (BARC) as a wild vagrant (BARC, 2014). although the geography raises the strong possibility of ship-assistance as well.

Within the region, as far as we are aware, the only records within the Malay Peninsula are from Singapore.

Overview of records

The Sisters’ Island bird was recorded on 28 Nov 2018 by Camphora Pte Ltd/Lim Kim Seng and was published in Feb 2020 (Lim, 2020). The grey fringes to the outer coverts and grey rump, and rufous edging to inner coverts narrower than in the resident erythrocephala and agricola, shown in the photograph available online, suggest the identification as an orientalis Oriental Turtle Dove. The strongly-contrasting covert fringes and fully developed neck-patch were consistent with an adult bird.

The Rower’s Bay/Neo Tiew bird was sighted twice, on 8 Jan at Rower’s Bay Park, by ksong, and 4 Feb 2023 at Lim Chu Kang Lane 3, by Lee Hua Keong. The similar forehead abrasion evident in both sightings led our committee to consider these records related. Like the previous record, the covert pattern suggested this bird belonged to the orientalis race as well, with wide covert fringes and a fully developed neck-patch pointing to an adult bird.

Most recently, the Labrador Park bird was sighted on 27 Jan 2024 by Elijah Chua and remained until 30 Jan. This record was also assigned to an adult orientalis with broad rufous inner covert fringing giving way to grey outer covert fringes, grey rump, and complete, well-defined neck patch.

Assessment of records (Rower’s Bay/Neo Tiew, Labrador Park)

There are three possible explanations for the provenance of each of these individual birds: unassisted natural vagrancy, ship-assistance, or captive origin. These were all considered in each of the records, as listed below.

Rower’s Bay/Neo Tiew bird

The Rower’s Bay/Neo Tiew bird was the first Oriental Turtle Dove record to be assessed by the full RC. Along with the lack of feathers on the forehead, the wear pattern on the wings appeared unnatural, particularly on the lesser and median coverts. The photos also suggested the bird was fairly tame, rather unlike the behaviour of migratory Oriental Turtle Doves in Indochina, or vagrant birds in the Philippines (A. Jearwattanakanok and M. Kennewell, pers. comms.). The RC regarded this information with suspicion of captive origin, especially since forehead abrasion is unusual in wild birds but common in captive birds as a result of repeated impact with the bars of a cage, and the committee concluded the bird was most likely an escaped individual.

Labrador Park bird

The Labrador Park bird was assessed earlier this year. The feathers and bare parts were noted to be in pristine condition, but the bird was extremely tame, with some photos showing observers within half a metre or less from it. Several observers noted it was nearly trampled on a few occasions. While some level of habituation is normal in city populations of the Oriental Turtle Dove in, for example, Japan and Taiwan, these populations are also non-migratory and would be unlikely to occur in Singapore naturally in the first place; this level of habituation with humans does not align with the migrants and vagrants elsewhere in Asia. Due to these concerns over the bird’s behaviour, this record was also relegated to escapee status.

Ship-assisted or escapee?

These individuals were regarded as escapes as this is the default for records which are deemed as ‘not wild’. While we acknowledge that unnatural feather wear and unusual tameness could occur in ship-assisted individuals as well, distinguishing between these two possibilities – ship-assistance and captivity – is essentially impossible in these two cases. Unless there is a clear reason to doubt captive origin (as in the case of the Sisters’ Islands record, based on the location), the RC’s stance is to categorise the records as likely originating from captivity.

Oriental Turtle Doves in trade

There is no evidence, based on surveys of pet shops, that Oriental Turtle Doves are traded locally. Indeed, the species seems rare in captivity – but not absent – in the wider region. However, the same can be said of several other species which are certainly escapees in Singapore based on their ecology; the Northern Red-billed Hornbill Tockus erythrorhynchus, Livingstone’s Turaco Tauraco livingstonii, and King Bird-of-paradise Cicinnurus regius are all unrepresented in surveys of local pet shops. Whereas presence in trade, whether local or regional, does raise the possibility of captive origin, we cannot discount captive provenance just because a species is unrecorded in the surveys.

Assessment of record (Sisters’ Islands)

The review of the Sisters’ Islands bird came after these two other records.

Sisters’ Islands bird

Singapore’s first record, from Sisters’ Islands, was reassessed earlier this year as well. Based on our communications with an observer of that bird, it was fairly skittish, as would be expected from a wild bird. There is no evidence to suggest unnatural feather wear or damage to bare parts, although given that only one blurry photograph is available, it is impossible to be sure that there is really none. Captivity would not be a likely explanation for this record given the location on an unpopulated offshore island. On the other hand, its proximity to one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world increases the likelihood of a ship-assisted provenance. The next step was to determine whether ship-assistance or natural vagrancy was more likely for this bird.

Ship-assistance in the Oriental Turtle Dove

Records of the Oriental Turtle Dove in North America are discussed in Howell et al. (2014). One record is of a bird on a ship off the Pribolof Islands in the Bering Sea, and ship-assistance is suggested as an explanation for other records in northwestern Canada. The authors comment that birds which are vegetarian, like doves, “almost certainly survive better on boats than insectivores and species needing animal protein (falcons excepted)”, which is a widely-held belief. Regarding the ages of the birds involved, “at least 2 of the 3 late fall–winter records from BC [British Columbia, Canada] and CA [California, United States] involve 1st-year birds, which may represent misoriented (reverse?) migrants.” It is well-documented that in most species, 1st-winter birds are disproportionately represented among vagrants (Veit et al., 2022); this appears to be the case for the Oriental Turtle Dove as well, a point further reinforced by the age breakdown of records in the UK (Naylor, 2024). The Sisters’ Island bird, like both the other birds in Singapore, was an adult.

Ship-assistance of other species in Singapore

Singapore’s first Long-eared Owl Asio otus was regarded as likely to have landed in the country with the help of a ship. Some of the introduced species in Singapore, such as some of the African seedeaters, may also be ship-assisted rather than genuine escapes from captivity.

Review of citizen science data

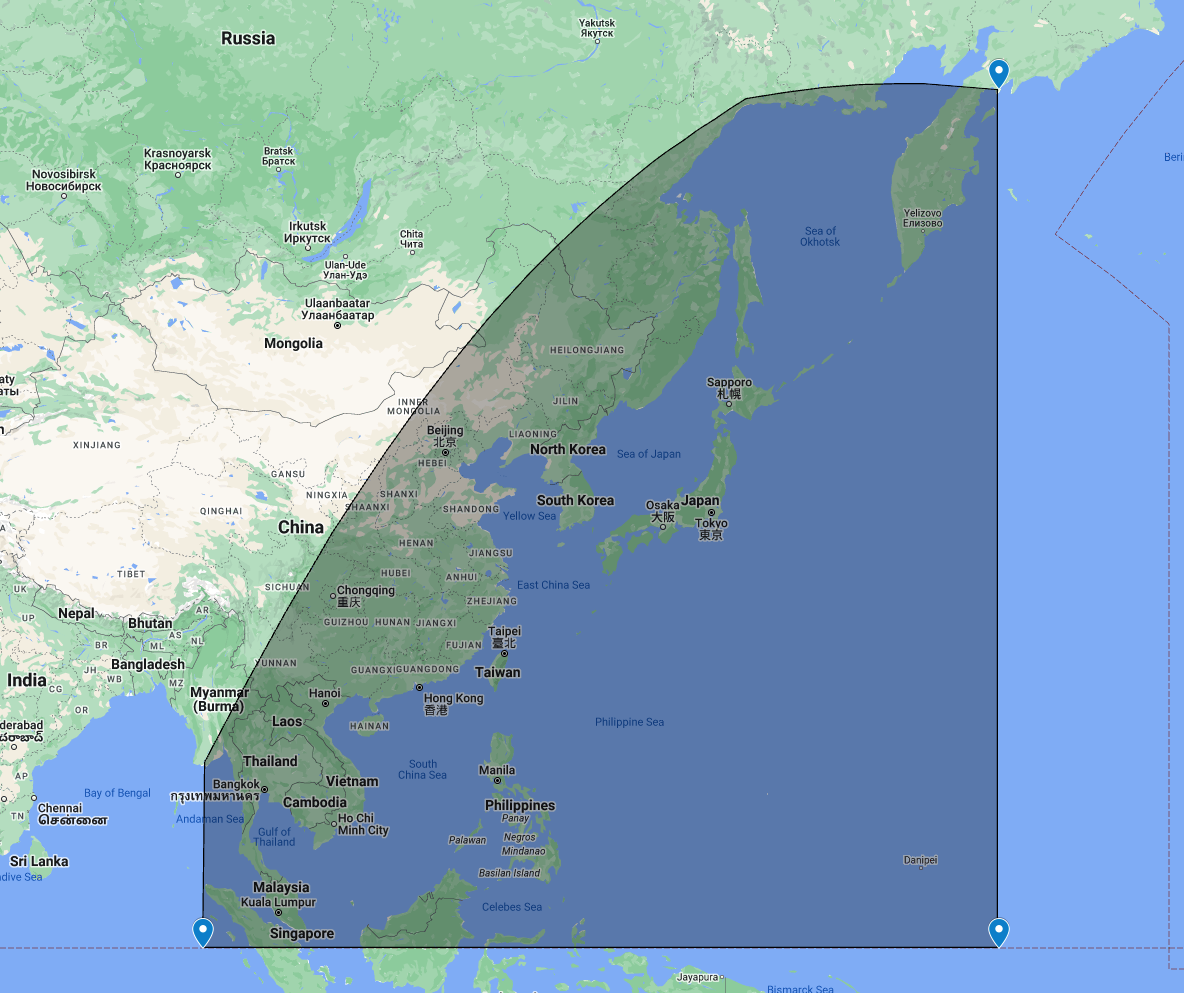

Citizen science data is quite sparse away from land, but sufficient for making general comparisons between different species. We compared the number of eBird records from the sea between latitudes 0–60º N, longitudes 95–165º E, for different species which are common in east Asia. A large number of these records are of birds sitting on ships, although some are not (e.g., birds flying over the sea); see Methodology notes. We did not analyse records in the Indian Ocean, where observations are too sparse to draw meaningful conclusions.

This table lists the number of sea records and individuals for each of the species, based on the full eBird dataset until January 2024.

| Species | Records at sea | Individuals at sea |

| Eurasian Tree Sparrow Passer montanus | 149 records | 429 individuals |

| White Wagtail Motacilla alba | 146 | 231 |

| Brown Shrike Lanius cristatus | 141 | 234 |

| Oriental Turtle Dove Streptopelia orientalis | 108 | 225 |

| Daurian Redstart Phoenicurus auroreus | 38 | 70 |

| White-cheeked Starling Spodiopsar cineraceus | 17 | 27 |

| Red-flanked Bluetail Tarsiger cyanurus | 10 | 17 |

| Lanceolated Warbler Locustella lanceolata | 10 | 12 |

| Japanese Tit Parus minor | 6 | 6 |

| Long-eared Owl Asio otus | 5 | 11 |

| Red-billed Starling Sturnus sericeus | 4 | 10 |

Oriental Turtle Dove is indeed quite a commonly-recorded species on ships in east Asia, with other similarly common species appearing lower on the list. We did attempt to find the most frequently ship-assisted species using eBird maps, and were unable to find any other species that appear more frequently than the Oriental Turtle Dove in east Asia among the migratory species that do not regularly occur in Singapore. The Daurian Redstart is also quite frequently recorded, but still significantly less often. The Long-eared Owl is recorded infrequently, which is to be expected, as a low-density species. Eurasian Tree Sparrows are common on ships, as expected due to their diet and association with urban environments.

The eBird data also suggests this species can fare well on ships over long distances, with one documented bird crossing the entire width of the Pacific Ocean on a container ship from 10 to 16 May 2016. Given the volume of maritime traffic between the busy east Asian seas and Singapore, a bird could easily make that transit in a similar span of time. Granivorous species, like the Oriental Turtle Dove, also tend to spend longer on ships compared to insectivorous species (Lees & Gilroy, 2009).

Committee’s assessment

With multiple sources suggesting the Oriental Turtle Dove is a frequent hitchhiker aboard ships, as well as the cases of two separate subsequent records with behaviour- or plumage-related abnormalities, the RC concluded the Sisters’ Island bird was likely a ship-assisted individual. The location, close to one of the world’s busiest shipping routes with massive volumes of maritime traffic originating from east Asia, also played a part in this conclusion; the lack of records across central and southern Thailand, despite several well-surveyed areas of suitable habitat, also did not help the argument for a wild bird. While the timing of the record, in November, is consistent with vagrancy, it is equally consistent with ship-assistance – most birds on ships are exhausted migrants that stop for a rest during their journey. The challenge of assessing records of short and medium-distance migrants, especially those which regularly migrate over east Asian seas, is clear – while vagrancy is obviously possible in these species, the probability of ship-assistance can never be ruled out. In the case of this species, the weight of evidence suggesting it frequently benefits from such human assistance was too great to ignore.

Maintaining a consistent treatment with other records was considered extensively by the RC. Records of Black Redstart Phoenicurus ochruros (Pasir Panjang, Nov 2021–Feb 2022) and Common Starling Sturnus vulgaris (Marina East Drive, Dec 2021), that were accepted as wild birds, were carefully reconsidered. In the Common Starling’s case, the case for wild provenance in this bird was the growing number of vagrant starlings added to Singapore’s avifauna in recent years, coupled with recent records in Peninsular Malaysia and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (eBird, 2024). For the Black Redstart, it was the concurrent influx of other vagrants which typically migrate from central and east Asia to winter in the Indian Subcontinent and further west in late 2021, such as the Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis and Spotted Flycatcher Muscicapa striata (Sin et al., 2021). For example, theoretically, an Oriental Turtle Dove of subspecies meena in 2021, particularly a first-year bird, would have had much stronger credentials for a wild provenance compared to any of the three confirmed records in Singapore.

Conclusion

The SBRC concluded that the Oriental Turtle Dove is unlikely to have occurred in Singapore naturally. The first record from Sisters’ Island likely arrived with the benefit of human assistance, and the subsequent records were regarded as likely escapes from captivity. The species is now placed in Categories E1 and E2, given the varying conclusions on the records under consideration, and removed from the Singapore Bird Checklist. Nevertheless, as always, further records of the species in Singapore, or evidence of vagrancy within the region, will continue to be scrutinised carefully.

Notes on methodology

Records of possibly ship-assisted birds were filtered from the eBird Basic Dataset (eBird, n.d.) using multiple layers of filtering. As many of the checklists lack details on whether the birds were actually sitting on the ships or just flying past, all sea-based checklists are included – we did not attempt to filter the checklists further, but records of 20 or more individuals were omitted. For the number of individuals, records with ‘X’ were treated as 1 individual.

Acknowledgements

The Records Committee would like to thank the observers for their timely sharing and submissions to our database, and our panel members for their advice.

References

Berka, P, & Horal, D (2023). The Oriental Turtle Dove (Streptopelia orientalis) – a new breeding bird species for the Czech Republic. Crex, 40, 203–210.

BirdLife Australia Records Committee. (2014). Submission No. 838 Oriental Turtle-dove Streptopelia orientalis. Link

eBird. 2024. eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Link

Howell, S. N. G., Lewington, I., & Russell, W. (2014). Rare birds of North America. Princeton University Press.

Lees, A. C. & Gilroy, J J. (2009). Vagrancy Mechanisms in Passerines and Near-Passerines. In: Slack, R. (Ed.) Rare Birds, Where and When: An analysis of status and distribution in Britain and Ireland. Volume 1: sandgrouse to New World orioles. Rare Bird Books, York.

Lim, K. S. (2020). Bird Records Committee Report (Feb 2020). Link

Naylor, K. A. (2024). Historical Rare Birds: Oriental Turtle Dove. Link

Sin, Y. C. K., Narayanswamy, R., Ng, D., Chia, S., Ng, E., & Kennewell, M. (2022). Beyond the pandemic: gems from Singapore in 2020-2021. BirdingASIA, 37, 101-108.

Sin, Y. C. K. & Ng, D. (2021). Singapore Birds Database: A Digital Museum of Local Bird Information. Link

Veit, R. R., Manne, L. L., Zawadzki, L. C., Alamo, M. A., & Henry, R. W. (2022). Editorial: Vagrancy, exploratory behavior and colonization by birds: Escape from extinction? Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10. Link