By Laura Berman

Bird song is one of the things that people love most about birds. Song is also a central aspect of bird ecology. Birds use vocal signals to communicate, send out warnings, attract mates, and defend territories. Knowing that, it isn’t surprising that noise pollution can have big effects on how birds behave, and how successful they are in a habitat.

Noise pollution from things like heavy traffic and airports can push birds into singing at quieter times of day, singing at different frequencies, or even shrink territory sizes or push birds into quieter habitats altogether.

But it isn’t only humans that are loud – natural things like waterfalls and even insects can produce enough noise to affect the way birds sing. A recent study based in Singapore and Brunei (Berman et al. 2024) found that some bird species will avoid singing together with loud droning cicadas. Which bird species are affected depends on the frequencies that those birds use in their songs.

Frequency-specific avoidance

Just like birds have species-specific songs, cicadas have species-specific tymbalizations, which use specific frequency bands. Birds will avoid singing together with cicadas when their frequency bands overlap.

That means that a bird like the Black-capped Babbler which sings at 3- 4 kHz would avoid singing with a cicada whose tymbalization also covers 3-4 kHz. This makes intuitive sense. Signals are more effectively masked by noise energy in the spectral region of the signal. When overlapping songs are using the same frequencies, they are harder to hear. Birds adjust their behavior to avoid being drowned out.

Saturating drones

But wait. Not all cicadas are loud enough to be worth avoiding. Like waterfalls and traffic noise, cicadas need to saturate a frequency band before they start to drown anything out. Acoustic saturation refers to how much of the acoustic space is filled with sound. For cicadas, saturation can depend on the structure of the tymbalization and population density.

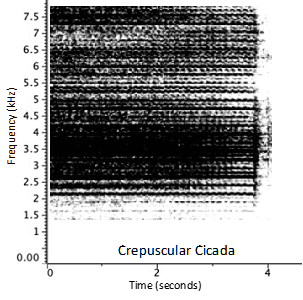

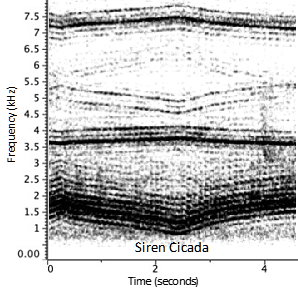

Some species, like the crepuscular cicada heard in Brunei, have a drone with extremely dense harmonics which saturates a broad frequency band. Other species, like the siren cicada in Singapore, have a more tonal call which occupies only a small percentage of the acoustic space. Only the first species can drown out birdsong and is worth avoiding.

Crepuscular cicadas have a tymbalization with many harmonics which saturates the majority of the acoustic space from 2 kHz to 8 kHz. Birds that sing at frequencies above 2 kHz generally avoid chorusing with crepuscular cicadas.

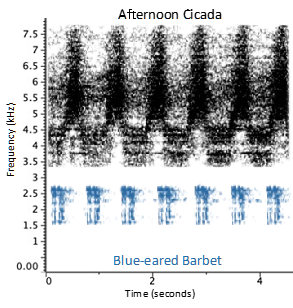

Afternoon cicadas also have a loud droning tymbalization, but Blue-eared Barbets don’t mind co-chorusing with these cicadas because they use non-overlapping frequency bands. The afternoon cicada uses frequencies 3.5 – 7.5 kHz, and the Blue-eared Barbet uses frequencies 1.5 – 2.5 kHz.

Not all cicadas are worth avoiding. Siren cicadas saturate less of the acoustic space – notice all the white space in the spectrogram. Most birds don’t mind chorusing with this cicada.

A multi-species soundscape

Next time you are out birding and have your ears tuned for the melodies of a Straw-headed Bulbul or Greater Racket-tailed Drongo, keep an ear out for the cicadas and katydids as well. The soundscape is made up of not just birdsong, but songs from insects, frogs and bats as well. The birds are already listening.

References

Berman, L. M., Tan, W. X., Grafe, U., & Rheindt, F. (2024). Rainforest birds avoid biotic signal masking only in cases of high acoustic saturation. Journal of Ornithology, 1-12. Link