Written by Keita Sin

The Bird Society of Singapore partnered up with eBird, managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, in October 2025! We started the collaboration with our BirdSoc SG October Big Day event in line with eBird’s annual October Big Day. These eBird Big Day events not only aim to promote the usage of the platform globally, but also aims to raise awareness and provide tips on the best birding practices.

We’ve previously written about the benefits of using eBird, and our team frequently uses data from the platform to make them easily accessible through our bar charts and Singapore Bird Database. But what exactly does it mean now that we have partnered up with eBird?

Our key responsibilities include outreach, mentorship and moderation efforts. We will continue preparing various useful articles and carry out our walks, talks and booths moving forward. In these mediums, we will start integrating eBird usage more so that everyone can get a better hang of how to best use the platform. In our moderation efforts we aim to improve the quality and reliability of the local eBird database. Primarily, we’ll be tightening the eBird filters (species and counts that will be “flagged” observations). This will mean that you’ll start to see some changes in the birds that might trigger “flags” in eBird – more of which we will explain in our upcoming articles. You might also start to receive emails from our BirdSoc SG eBird moderators regarding your past observations, where we might request for additional evidence such as descriptions or media to support the records. Please bear with us as we work on the past few years’ data while concurrently to moderate the new submissions. Our aim is to improve the accuracy of Singapore’s database as these can have very important implications on both scientific and conservation efforts. And as always, feel free to let us know if you have any feedback!

When you submit your records on eBird, the data that you upload to the portal doesn’t always get accepted immediately. Certain records will be flagged by the system, and regional moderators have the responsibility to accept or reject those records to maintain the quality of the eBird database. Oftentimes, we can assess the records based on the media (photo/audio) attached or the descriptions provided. In other cases, the flagged bird might have already been properly documented by previous birdwatchers, and birds that are “continuing” (i.e. the same bird individual observed again by others) can also be quickly accepted. However, there are many cases where the lack of information makes it impossible for us to determine its validity. In such cases, we will need to contact the observers to request for additional details.

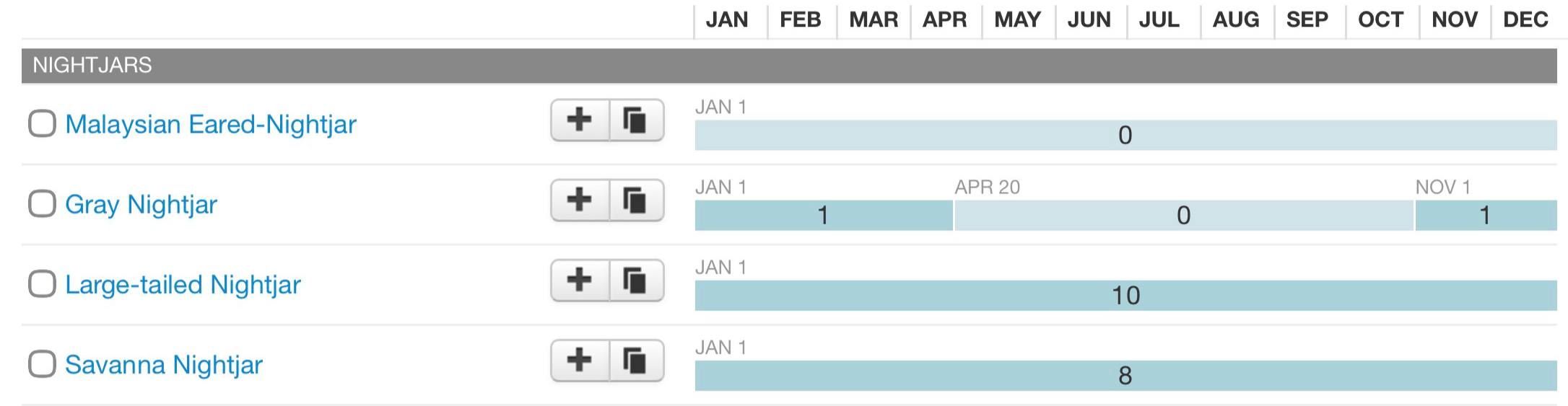

In the eBird system, moderators can set up different filters that will trigger warnings when a checklist is being prepared. These filters work either by detecting unusual species or counts and are partitioned across different times of the year to account for seasonality.

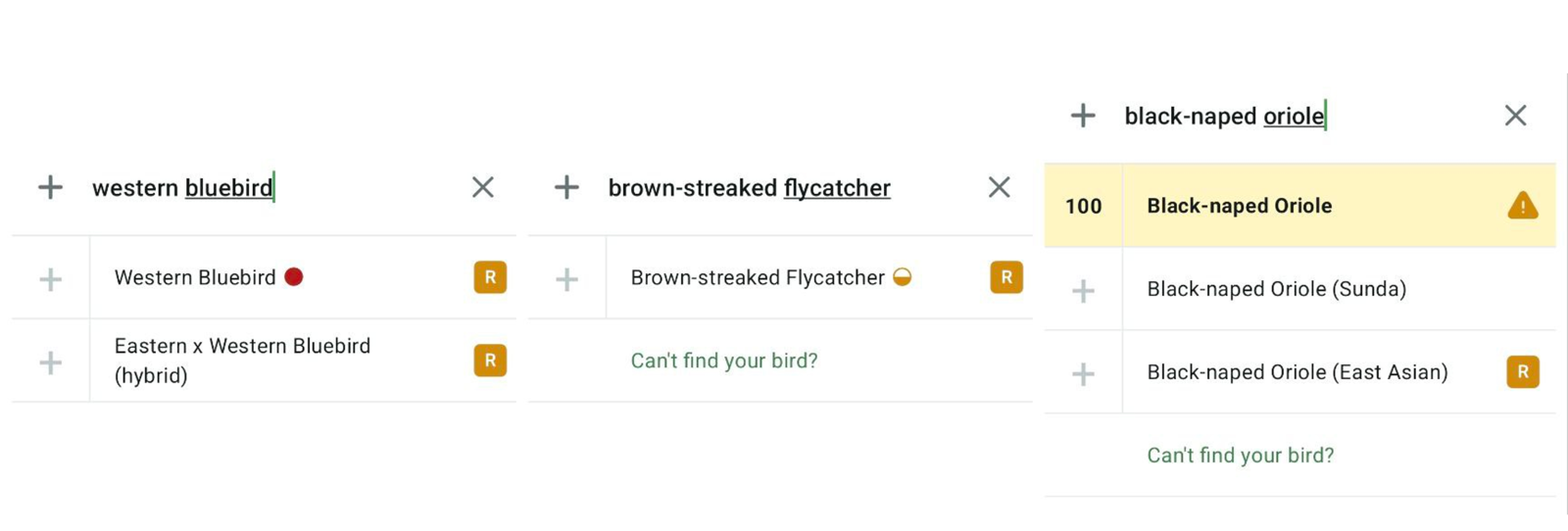

The first and most obvious case of a record that will be flagged is a completely unexpected or very rare species in Singapore. For example, a Western Bluebird reported in Singapore needs to be properly verified. It could have been a mistake when attempting to key in the Asian Fairy-bluebird, or it could perhaps be a bird that was somehow released locally. If a Taiga Flycatcher is reported, it needs to be properly assessed too. Even though it is a species that has been recorded in Singapore before, its sheer rarity and similarity with other flycatchers warrants a rigorous confirmation process.

There are also some birds that are annually documented in Singapore, but considerably unexpected at certain times of the year. Species like the Brown-streaked Flycatcher are mostly found in Singapore around August and September. Many records from the winter and spring months are much more likely to be the commoner and similar looking Asian Brown Flycatcher. Records of the Brown-streaked Flycatcher outside their typical season will hence need to be strongly substantiated. In a similar vein, the three species of Pond Herons cannot be identified in their non-breeding plumage. They are generally only identifiable in spring, from around March to May each year when they start to acquire their breeding colours. Records that identify any of the three Pond Herons to species level during the autumn/winter months hence need to be verified.

Additionally, certain species are regular in Singapore but can be easily misidentified. The scarce Asian Palm Swift is a good example, where the very common “Blackible” swiftlets (Aerodramus sp.) could be easily mistaken as one instead. Hence, reports of this species will need proper assessment.

Additionally, certain species are regular in Singapore but can be easily misidentified. The three species of Hawk-cuckoos that occur locally in winter are good examples where a combination of features including their size, bill and tail are needed for identification.

Sometimes, you could be reporting a very common species, but at a number that seems unrealistic. Seeing 100 Black-naped Orioles in one morning at Jurong Lake Gardens, for example, is highly unusual. It could well have been a typo error for 10, or there truly could have been a massive flock passing through. In the latter case we would need proper evidence or descriptions to accept the record.

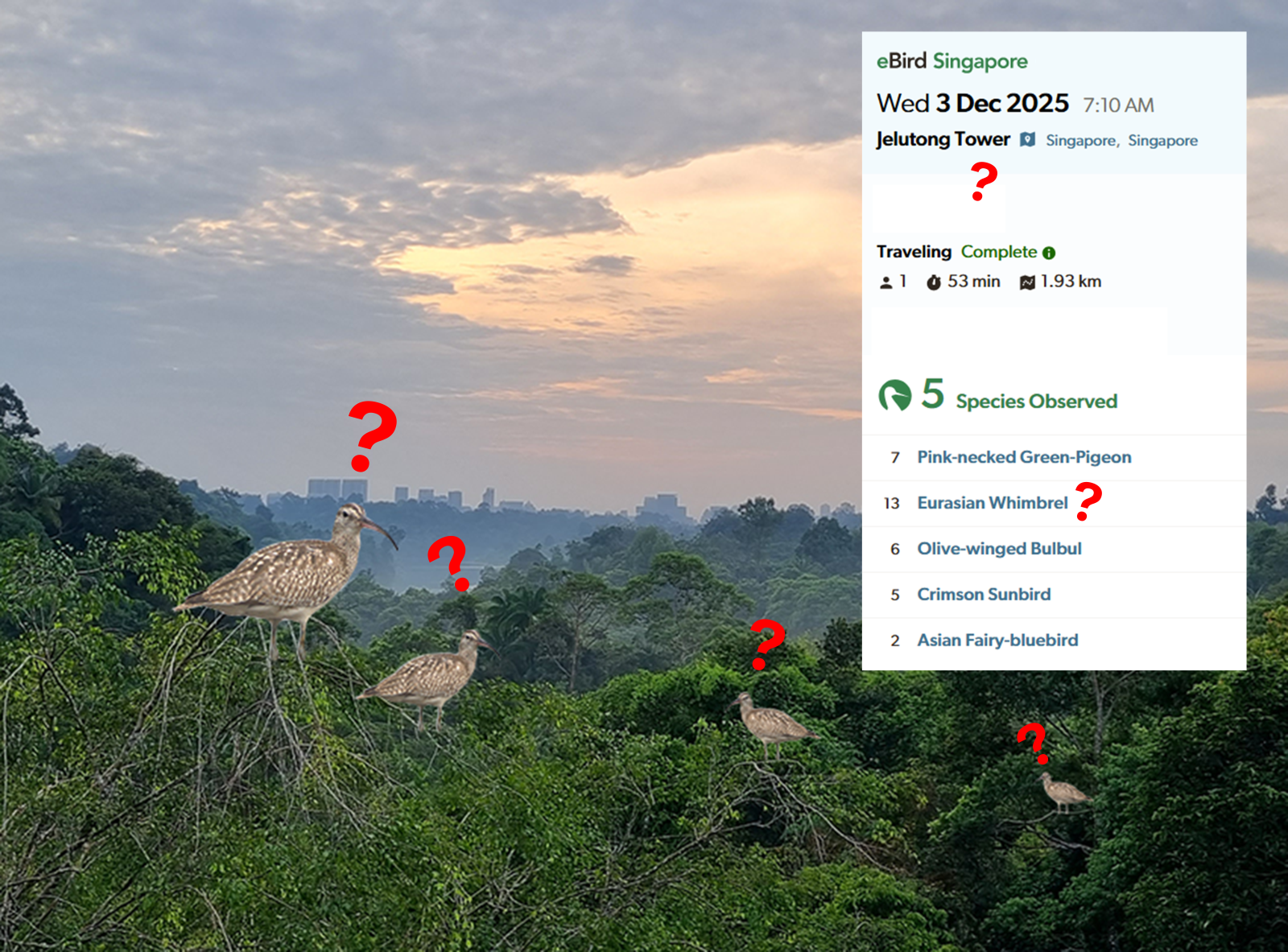

A slightly more problematic case would be a mega-checklist leading to common birds being reported at unanticipated locations. Let’s say you started your birdwatching session at MacRitchie Reservoir and chose the Central Catchment Nature Reserve hotspot for checklisting. If you head over to Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve afterwards for birdwatching but fail to split up the checklist into different hotspots, it will egregiously mean that a flock of Common Redshanks or Eurasian Whimbrels was seen in the middle of Singapore’s old secondary forest. Such records will also be flagged and need to be fixed.

How can we then best make sure that such records are properly assessed? When you key in unexpected records into eBird, you would notice warning messages such as “rare” showing up on the platform. When these messages show up, we strongly urge you to enter detailed descriptions or upload media evidence (photos/audio) to substantiate your record. These will be extremely helpful for us moderators when assessing the record, and will also save us both the trouble of having to re-evaluating these checklists afterwards. When you do receive an email from us, we would be very happy if you could update the checklist with additional evidence. We’ll then be able to re-check the record from the eBird system.

Very importantly – and this is something that really needs to be stressed – an email from us is in no way an indication that we are doubting your identification or birdwatching ability at all! Our job is to assess all the records using an objective framework so that the database can be trusted by any neutral party. Additionally, even if we decide not to accept your record on eBird due to insufficient evidence, that doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t count the bird for yourself. We strongly believe in the following mantra “your list, your rules”: You as an individual birdwatcher know best what you observed, and nobody else should tell you what to do. Having said that, we’re definitely always happy to have discussions regarding identification and observations – those are the very conversations that can drive ideas and subsequent work.

Having a high-quality eBird database can be extremely beneficial to researchers and government officials to aid local conservation and science. A prime local example is this work that was published by researchers from the National University of Singapore, in collaboration with the National Parks Board and Singapore’s former eBird moderator.

The Bird Society of Singapore partnered up with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in October 2025 and are now part of the local moderating team. We’re excited to carry out this work to improve the quality of Singapore’s database and look forward to working with all of you.

We’ll be uploading more eBird tips in the coming months, so watch this space!!